talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

http://www.ushmm.org/

Created and maintained by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

Reviewed Oct. 2010–Jan. 2011.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), the nation’s largest public institution dedicated to Holocaust remembrance and scholarship, serves multiple constituencies, as does its Web site: visitors to the USHMM’s exhibitions and public programs, scholars wishing to use its collections or participate in its Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, educators and students researching the Holocaust, survivors of the Holocaust or their families seeking information about the lives and deaths of individuals during the war, people concerned about ongoing cases of genocide.

The site provides information that pertains directly to the physical institution — directions and hours, online versions of exhibitions, catalogs of research collections, inventory of the museum shop — and serves as a virtual extension of the USHMM’s public role. In this capacity, the site is a major resource for online users of all kinds — especially as the site is the first or second listing to appear on Google searches of the term “Holocaust” — who seek information on the history of Holocaust, resources for Holocaust pedagogy and scholarship, or news about genocide prevention. The USHMM’s site includes an online Holocaust encyclopedia (with 667 entries in English, plus versions in over a dozen languages, including Arabic, Chinese, Indonesian, and Turkish), organizes its educational materials according to categories of user (teachers, students, university scholars), anticipates inquiries with a roster of frequently asked questions about both the Holocaust and the USHMM, and provides a “Virtual Reference Desk Request Form.” The museum also engages its constituents through popular social media platforms (Twitter, Facebook, Delicious), posts media on YouTube and iTunes U, and even has a presence in the virtual world of Second Life. In addition, the site elicits information and resources (photographs, for example) related to the Holocaust from users and provides opportunities for donating to the USHMM.

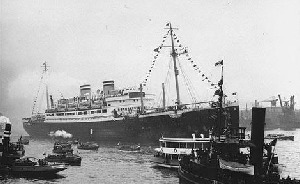

Photo of the St. Louis from the “Voyage of the St. Louis — Animated Map.”

The preponderance of information provided on the site is in the form of discrete texts or images (both still and moving) — that is, the online equivalent of what one might find at a library or archive. In addition, the USHMM offers online resources that make more elaborately integrated use of the Internet’s distinctive properties as a medium. Of particular note are the museum’s recent Mapping Initiatives, which use tools such as Google Earth and animated maps to enable citizens to understand Holocaust history and to bear witness to current threats of genocide across the globe. The Holocaust Mapping Initiative overlays key Holocaust sites and historic content from the Museum’s collections on Google Earth and other maps. The Genocide Prevention Mapping Initiative brings together data, photographs, video, and eyewitness testimony in Google Earth to help inform citizens, governments, and institutions about current and potential genocides and related crimes against humanity. Animated maps on Holocaust history include key locations (the ghettos in Warsaw and Lodz, the camps at Auschwitz and Dachau) and events (the ill-fated voyage of the St. Louis in 1939, the liberation of concentration camp prisoners in 1945), presented as short documentary videos that integrate narration and vintage photographs with maps. Using an interface with Google Earth, the USHMM site also provides background information and resource materials (vintage films and photographs, video of survivor testimony) on major sites in Holocaust history, alongside images of the sites today. This juxtaposition of past and present can be provocative, especially as the user shifts from the museum’s scholarly presentation of these locations' historical significance to the personal photographs and idiosyncratic comments that an array of contemporary users post on Google Earth of their visits to sites of Holocaust remembrance (for example, one such photograph of the campground at Auschwitz is labeled “F***ing Fences”).

Although the USHMM site is widely regarded in the United States as the largest and most authoritative online resource on the history of the Holocaust for both the general public and the advanced scholar, it is perhaps of greatest interest to the cultural historian or public historian not as a resource but as an artifact. The vast scope of information is noteworthy; like the visitor to the USHMM’s core exhibition, the site user can be, I think intentionally, daunted by its monumental scale. At the same time, the site is calibrated to enable easy navigation of its extensive offerings, articulating different levels of knowledge expected of the child, the adult, the teacher, and the academic. Moreover, as the online presence of a national museum, the site offers something of a national voice on the Holocaust and therefore exemplifies the place of Holocaust remembrance in American public culture. In particular, users can track how the USHMM seeks to fulfill its mission of fostering Holocaust remembrance as a moral paradigm. The home page provides “Combating Antisemitism” and “Preventing Genocide” links (with resources on recent or ongoing genocides in Bosnia, Rwanda, Chechnya, Congo, and Sudan). A link to “rescuing the evidence” of the Holocaust is given equal stature to these concerns, implicitly situating support of the USHMM as an act of social justice in itself.

Jeffrey Shandler

Rutgers University

New Brunswick, New Jersey