talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

Free Speech Movement Archives

http://www.fsm-a.org

Created and maintained by the Free Speech Movement Archives (FSM-A), Berkeley, Calif.

Reviewed April 15–19, 2002

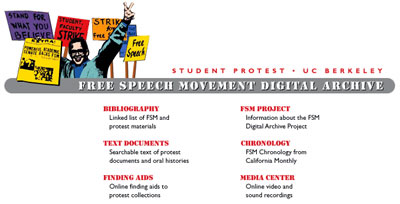

Free Speech Movement Digital Archive

http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/FSM

Created and maintained by the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley

Reviewed April 15–19, 2002

The free speech movement (FSM) at the University of California, Berkeley, in the fall of 1964 was a landmark of 1960s America. To a student of that era the FSM offers both protracted drama—with mass participation at numerous points and nearly eight hundred arrests in a single sit-in—and a conceptual bridge from the early-sixties civil rights movement to the late-sixties student revolt. Ideally, a Web site on the free speech movement can provide a fascinating window into a tumultuous period of U.S. history. Neither of the Web sites under review offers such a window, though each has its virtues.

The two sites’ similar names conceal very different (though not incompatible) purposes. The founders of the Free Speech Movement Archives (FSM-A) see their Web site as part of a still-living history of the FSM, embodied in the recollections and the ongoing lives of its participants. The site is a natural outgrowth of the twenty- and thirty-year reunions that many FSM veterans attended in 1984 and 1994.

The Web site faces in two directions. It seeks to serve its “core constituency,” defined as “the veterans and associates of the FSM”; at the same time, it seeks to help “make the FSM’s history accessible and useful, in and beyond educational institutions.” The first goal is seemingly more fully achieved. The site includes a “lost lambs” list of FSM participants whose whereabouts are unknown to the archives organizers and a list of deceased FSM veterans and friends. It provides opportunities for FSM people to tell what they are doing now. The memory of Mario Savio, the FSM’s most charismatic leader, who died in 1996, is kept alive through several pages on the site. All in all, the site represents a labor of love by a number of people for whom the FSM continues to represent a community of high ideals and mutual caring. The theme of ongoing commitment comes through strongly.

For outsiders (and no doubt for many FSM participants for whom the movement has faded in importance), the site is not easily mastered. The overstuffed home page includes approximately seventy-five links (along with a dozen or so links in formation that represent future plans rather than currently available pages). There is no natural starting point for a casual reader, no succinct overview with photos of what actually happened at Berkeley in 1964 and why it was important. A teacher who recommends the site to a student as a window on the FSM’s history may need to prepare a list of specific pages for the student to consult.

The site also suggests a familiar Web site cycle in which freewheeling enthusiasm is followed by inertia in regard to updating. The home page links to an announcement of a May 2000 reunion of SLATE, the campus political party that helped pave the way for the FSM, but there is no indication of whether the reunion was actually held. The fight for local control of Pacifica radio station KPFA (in some ways a logical extension of the free speech struggle) is traced in detail up to February 2001 and then dropped.

The Bancroft Library at Berkeley has an FSM site of its own, Free Speech Movement Digital Archive, funded by a portion of a $3.5 million donation from Stephen M. Silberstein, a former library worker (and FSM sympathizer) who went on to found a high-tech company. The Bancroft site consists mainly of digitized documents having to do with the FSM. The documents are quite extensive, but they are not organized in such a way as to invite the casual reader or the student. They are categorized by genre (“Leaflets,” “Letters,” “Press Releases,” “Minutes of Meetings,” etc.) irrespective of sources or chronology. Pre-sentencing letters from hundreds of students who were arrested in the massive Sproul Hall sit-in are grouped by letters of the alphabet—to no apparent purpose, since the names have been excised from all of them.

The Bancroft archive shows a degree of amateurism in its design. Some documents are unnecessarily divided into multiple pages. In these cases, not only does an outline of the document take up great amounts of space on each page but the user has no way to return to the archive’s home page without repeated use of the browser’s Back arrow (or its History button). A dedicated scholar can overcome these obstacles, at the cost of much annoyance, but it seems unreasonable to expect that students will.

There is a dry quality to the Bancroft archive, as if the Web were being treated as simply a different kind of storage facility. The FSM veterans’ archive, on the other hand, seems to project warmth and inspiration for some users but a certain amount of bewilderment for others. The two sites offer, respectively, a sharing device for veterans of the FSM and a set of supplementary documents for in-depth researchers. Both of those are worthy services, but neither does justice to the educational potential of the World Wide Web.

Jim O’Brien

University of Massachusetts

Boston, Massachusetts