talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

The Living Room Candidate: Presidential Campaign Commercials, 1952–2004

http://livingroomcandidate.movingimage.us

Created and maintained by the American Museum of the Moving Image, Astoria, N.Y.

Reviewed Sept. 1, 2004.

“I deeply, deeply resent—and am offended by—the attacks President Carter has made on my husband,” Nancy Reagan bristled in one 1980 campaign commercial. Nearly two decades ago, while writing my doctoral dissertation on presidential campaigning, I heard about that advertisement but could not track it down. Queries from coast to coast confirmed that the advertisement had been aired, but I failed to secure a copy. Similarly, years later, when I began teaching a course on presidential campaigning, I assembled a highlight reel of those campaign commercials I could find, not necessarily the most educationally useful ones.

The Living Room Candidate is thus doubly welcome, both as a research and as a teaching tool. Remarkably, at the click of a button, my students, colleagues, and I can now access 250 campaign commercials, representing four of the most politically influential hours broadcast over the last half century. One well-organized, easily navigated site presents the Democrats‘ and Republicans’ greatest hits—and misses. This site offers the usual suspects—the controversial 1964 pro-Lyndon B. Johnson “Daisy” commercial; the evocative 1984 pro-Ronald Reagan “It’s Morning Again in America” celebration; the inflammatory 1988 pro-George H. W. Bush “Willie Horton” attack. The site also offers some of the early, radio-influenced jingles from the 1950s and a host of easily forgettable commercials that have clogged the airwaves at election time, highlighting the great skill and good fortune needed for commercials to become defining and memorable.

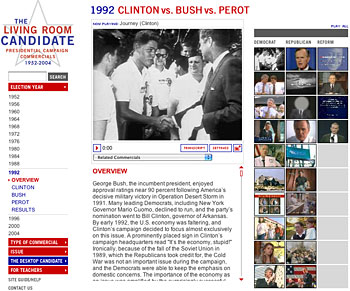

Here, the commercials for the 1992 campaign demonstrate

the site’s breadth and user-friendliness.

The year-by-year organization is most inviting, and the site remained updated, adding television ads and the harsher Web-based ads throughout the 2004 campaign. Yet the producers encourage longitudinal use—and thinking—by organizing commercials by Type of Commercial and by Issue as well. The categories are useful, if idiosyncratic. There is nothing wrong with categorizing commercials by Backfire, Biographical, Children, Commander in Chief, Documentary, Fear, and Real People. It is hard to quarrel with Civil Rights, Corruption, Cost of Living, Taxes, War, and Welfare as issues. Yet somehow, while no dramatic gaps emerged, both lists lacked an elegance, an economy, an implicit comprehensiveness, a consistent and parallel nomenclature that would make them definitive. Why Commander in Chief, not Leadership? Why War, not Foreign Policy? Why Corruption, not Honesty?

This site also should come with a warning. A Willie Horton history of campaigning only yields so much; electoral history, even in the television era, is more than the sum of its commercial parts. A newer, more comprehensive version of this site would expand the competent but brief introductions to each election by giving some more context, explaining the back stories behind some of the more successful commercials, providing survey results and poll results, and, most important of all, listing other sources, including some old-fashioned books and articles, that might place these ads in broader perspective.

Still, these are quibbles. This online exhibition of presidential campaign commercials is superb. My students will enjoy it and learn from it. I only wish I had had it at my fingertips years ago.

Gil Troy

McGill University

Montreal, Canada