talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

Raid on Deerfield: The Many Stories of 1704

http://www.1704.deerfield.history.museum

The Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association (pvma)/Memorial Hall Museum, Deerfield, MA

Reviewed Dec. 15, 2004–Jan. 10, 2005.

Raid on Deerfield is a brilliantly executed and comprehensively organized electronic exhibition. The Web site begins with a brief video background on the 1704 attack by the French and three Native peoples—Kanienkehaka (Mohawk), Wendat (Huron), and WĂ´banaki (Abenaki and others)—on the English settlement of Deerfield, Massachusetts. It then invites visitors to explore each of the five cultures in 2,500-word essays supplemented by artwork, maps, charts, and audio clips that pronounce unfamiliar words. Raid on Deerfield strenuously avoids privileging the Europeans and helpfully provides the Native peoples, especially the Wendat, with a history as well as an ethnography.

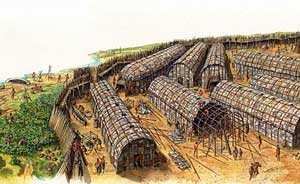

Wendake, a village of the Wendat people, circa. 1500. Illustration copyright Francis Back.

Alternately, or subsequently, visitors may proceed through ten “scenes,” which narrate the Deerfield raid and its origins and consequences from 1550 to the present. Each scene is, in effect, a superb Web site in itself. Moving one’s cursor over a painting of the scene invites in-depth exploration of the people and artifacts in the scene. Maps and background “explanations” for what is occurring are also easily at hand. Every event is presented in multiple perspectives.

I am afraid that one still has to visit Deerfield in person to have a connection to this history “in every sense.” That, of course, is the problem of the medium. As an exhibition developer, I depend upon a theory derived from environmental psychology to fashion informal learning experiences in space as an alternation of “prospects” (overviews) and “refuges” (immersions) (Jay Appleton, The Experience of Landscape, 1996). Visitors learn best when they can perch over a subject for a while, seeing its contours and pathways, and then nest themselves in intense, real-time encounters with historical events, characters, documents, and objects. Raid on Deerfield is all prospect and no refuge. Like many Web sites, this exhibit gallery is a hall filled with exit signs. The impatient Web visitor, accompanied only by her mouse, can leap in a trice from 1704 Deerfield to 2005 Delhi without compunction.

Compare John Demos’s valuable book on the Deerfield raid, The Unredeemed Captive (1994). Demos also tries to locate many beginnings for the raid story. But even a fine book cannot make all the actors appear on the reader’s screen at once, as this Web site does. On the other hand, once we begin to follow Demos’s exploration of the painful reflections of the Williams family survivors at losing their seven-year-old daughter and sister, Eunice, to her Kanienkehaka captors, we are gripped emotionally as we cannot be by the Web site.

The 22-year-old slave woman Parthena, owned by Rev. John Williams,

was killed in the Deerfield raid. Illustration copyright Francis Back.

Still, the undaunted explorer will find surprises even in this well-charted landscape. Like other historians, Demos notes the killing of Parthena, the Williams’s twenty-two-year-old slave woman, during the raid. We know nothing of Parthena prior to her arrival in Deerfield. The Web site constructs a splendid pre-Deerfield biography for Parthena from careful research in the history of slavery in New England. But it also poses a quandary: Why didn’t the Reverend John Williams, so grieved by the kidnapping of his daughter, see the resemblance between his loss and that of those other parents, perhaps in Senegambia, whose little girl became Parthena?

Richard Rabinowitz

American History Workshop

Brooklyn, New York