talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

Northern Visions of Race, Region, and Reform in the Press and Letters of Freedmen and Freedmen’s Teachers in the Civil War Era

http://mac110.assumption.edu/aas/

Created and maintained by the American Antiquarian Society Online Resource, American Antiquarian Society.

Reviewed Jan.–March, 2010.

This is a very useful Web site for introducing students to racial stereotypes in the Civil War-era North and to the important relationships forged between freedpeople and their teachers in the later years of the war and during the immediate postwar period. It is an archive – primary sources are displayed with minimal scaffolding – and an electronic essay, where explanations and context are provided for the primary sources. While the site is comparatively small, the sources are well framed and thoughtfully juxtaposed with classic documents from President Abraham Lincoln, rare letters written by freedpeople to their teachers, images from Harper’s Weekly, and rebuttals from Southern newspapers woven together as a response to a series of questions about Northern culture during the Civil War era.

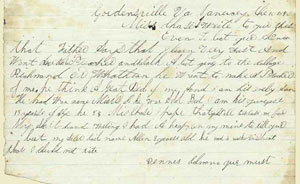

Dennis Adams to Freedmen’s Teacher Sarah or Lucy Chase, January, 1870.

The main sections of the site are “Freedmen,” "Freedmen’s Education,“ and ”At the War’s End,“ and an archival section titled ”Primary Sources.“ The ”Freedmen“ section first focuses on racial stereotypes, then looks at conversations that took place during the early to middle periods of the war, first on the issue of contraband and then on the Emancipation Proclamation. In each case the site includes perspectives from all sides, although the majority of opinions come from the North. Then the section turns to visions of the freedmen – as scholars, workers, moral citizens, and soldiers. The ”Freedmen’s Education“ section begins with framing – ideas about education, the pedagogy of the teachers, and their identities – and follows with a close look at Lucy Chase and Sarah Chase, sisters who left a rich store of their own and their students' letters. A final section, called ”At the War’s End," focuses on the ways the North saw the South, freedpeople, and reform in the later 1860s and 1870s. Some of it is troubling to read. Exaggeration, sarcasm, hatefulness: it is all here, sometimes in print and sometimes in sketches or comics. The site issues warnings about what the reader will find, but each piece is thoughtfully framed with explanation, and the shock value is educational. Here, the North can claim no moral high ground on questions of racial prejudice. Even though the site is primarily about the North, it makes a real effort at balance. Public documents from the Southern press are included here, along with letters between slave auctioneers and slave owners.

Overall, this is a moving, startling, and informative site – one helpful for scholars (especially those intrigued by freedmen’s education and the North) but perhaps best suited for students and their teachers. One useful feature allows the reader to open all topics under a heading or to open only those topics that pertain to the question that sparked their interest. Unfortunately, such selectivity is not possible in the primary sources section; instead the visitor must toggle back and forth between headings and topics.

Lyde Cullen Sizer

Sarah Lawrence College

Bronxville, New York