talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/amlaw/lawhome.html

Created and maintained by the Library of Congress.

Reviewed July 2010.

This massive collection covers one hundred years of American history from the formation of the Continental Congress through the Reconstruction era. Its primary focus is on lawmaking, from legislative action through the final publication of the law, and the collection is divided into four major components: the “Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention,” "Statutes and Documents,“ "Journals of Congress,” and “Debates of Congress.” In addition to state and federal laws, “Statutes and Documents” includes the thirty-eight–volume American State Paper series and the United States Congressional Serial Set. Besides the standard legislative records, the collection includes other important sources: Letters of the Delegates to Congress, 1774–1789, Farrand’s Records of the Constitutional Convention, and Elliot’s Debates—which includes state ratifying conventions as well as the standard congressional debate sources from the Annals of Congress, the Register of Debates, the Congressional Globe, and the Congressional Record. Some of the collections, especially the material in the U.S. Serial Set, include documents that date to the early twentieth century.

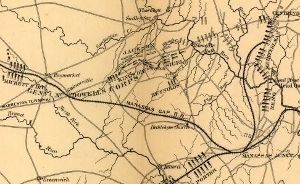

“Position of troops at sunset August 28th, 1862. [Second Manassas battle]”

From 38th U.S. Congress, 2nd session, report 142.

As the product of the Library of Congress, the Web site is designed to be used by researchers with a minimum of technical skill. Visitors can click on each record to find a short collection description, including prompts to related information sites, and directions on how to use the collection efficiently. They can browse or search a collection. If using transcriptions, they can click to the original page image and then move forward or backward in the document. Searches often offer links to other date-related documents. There are additional tabs to take the viewer back to the collection to undertake a new search or to return to the opening page of the collection. The pages are printable. There is also a “contact us” link.

The search feature is deceptively simple and very powerful. Legislators, issues, dates, or just topics can be linked in a search. I entered “secession” just to see what the records would show and was pleasantly surprised to find a link to the Confederate Congress set which was not listed as part of the legislative set of A Century of Lawmaking. Despite the fact that the Annals of Congress series has not been digitalized, it can be searched through its index with very good results.

There is also a tab to the Library of Congress’s American Memory Digital Collection. Clicking on “Presidents,” for instance, leads to various manuscript collections (such as the Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Lincoln Papers), most of which are searchable, as well as broadsides and printed ephemera from the rare books collections. Not every broadside owned by the Library of Congress, however, has been digitized or is online. While the majority of the American Memory collection relates to nonpolitical topics, it is an invaluable supplement to this collection.

There are two unexpected treasure troves in A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation. The first is the Appendices of the Debates of Congress series. Inauspiciously described in the early Congresses as “comprising the most important documents originating during that Congress,” the appendices contain a wealth of material that goes far beyond what one would expect to find in the legislative debates. There are documents on the impeachment of William Blount; material on the Louisiana cessation, the Aaron Burr conspiracy, the Lewis and Clark expedition, abolitionist petitions, and fugitive slaves, as well as regular reports on foreign relations and governmental matters.

The second treasure is the U.S. Serial Set. Among other things, it contains the Journal of the Congress of the Confederate States of America, 1861–1865, which would not be listed as part of the Journals of Congress series; various reports from the Civil War era; Francis Wharton’s Revolutionary Diplomatic Correspondence of the United States; Indian Land Cessations in the United States, 1784–1894; as well as reports on western land and other matters. The set includes material from the twenty-third Congress (1833–1835) through the sixty-fourth Congress (1915–1917).

One challenge of any legislative history is the proper identification of the individual legislator. It is unfortunate that the standard guide, The Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress, 1774 to the Present, is difficult to find. It is listed under “Related Resources on the Internet,” and then far down the page, under “External Web Sites.” It should be more easily accessible. It is also unfortunate that it is linked to the current House of Representatives Web site rather than to a digital copy of an earlier printed edition. The site is designed to identify an individual legislator, but it does not provide the supplemental information found in earlier printed editions. These editions listed state delegations by Congress and identified congressional officers, as well as the members of the executive branch, by administration.

It would also be very useful to include either digital copies of various biographical collections or at least to refer to them in the Selected Bibliography section. For instance, volume fourteen of the Documentary History of the First Federal Congress series offers more extensive entries on members of the First Congress than are found in the Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress. This challenge is equally true for the Constitutional Documents section that lists the Biographical Directory under "External Web Sites." Surprisingly, there is no link to the online Constitution Center, which has entries for each founder. It would also be very helpful to refer to Bernard Bailyn’s two volume set, The Debate on the Constitution (1993), which includes insightful biographies of the major participants in the debate over the Constitution. It should be digitalized and made part of this collection.

It is easy to quibble with any effort to create a selected bibliography for each of these units; most listings are generally appropriate and reflect attention to contemporary scholarship, but several books should be included. The “Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention” section surprisingly makes no reference to Merrill Jensen’s Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution (21 vols., 1976–), Bernard Bailyn’s The Debate on the Constitution (2 vols., 1993), or Philip B. Kurland and Ralph Lerner’s The Foundersí Constitution (5 vols., 1987), all of which are major primary source collections on the subject. The adoption of the Bill of Rights also appears to have fallen between chronological categories. Helen E. Veit, Kenneth R. Bowling, and Charlene Bangs Bickford’s Creating the Bill of Rights: The Documentary Record for the First Federal Congress (1991) and Neil H. Cogan’s The Complete Bill of Rights: The Drafts, Debates, Sources, and Origins (1997) should be included.

It is also surprising that twenty-five volumes of Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774–1789 (1976–1995) have been digitalized but not the twenty-sixth volume, which is the cumulative index for the series.

A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation is a truly impressive enterprise. Both in terms of its contents and the ease with which visitors can search or browse the collections, it offers a wealth of material for online research. The Library of Congress site has a special link for teachers and researchers that offers supplemental information and support.

Whitman H. Ridgway

University of Maryland

College Park, Maryland