talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

The American Family Immigration History Center

http://www.ellisisland.org/

Created and maintained by the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., New York, New York.

Reviewed Aug.-Sept. 2009.

During its years of operation, 1892–1954, Ellis Island served as the disembarkation point for over 12 million immigrants hoping to make America their home. For the first time, the records of their arrivals and of the ships on which they journeyed have been made available to the public through the establishment of the American Family Immigration History Center (AFIHC). The center’s holdings include scanned versions of original ship manifests, individual passenger accounts, and descriptions (often accompanied by photographs) of the ships that carried the newcomers to the United States. Anyone interested in American history or genealogy will find much here.

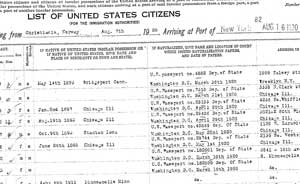

Detail of the August 1920 ship manifest for the Bergensfjord.

While access to the records of the AFIHC was opened in 2001, those interested in seeing them had to visit the Ellis Island Immigration Museum, located off the shore of Manhattan. Now this can also be accessed electronically. Searching and viewing the database cost nothing, although the site requires that visitors register and create a username to view individual records. The basic search engine operates by culling data entered by the researcher, such as an individual’s name, gender, and, if known, the approximate year of birth. A list of results appears and the researcher has the option to view any of the documents pertaining to their query, including the manifest, immigrant record, and ship profile.

If a basic search yields no results, visitors can also use an advanced search engine to find individuals. This can be useful when looking for people with surnames that might have been recorded incorrectly on the manifests or that could be spelled in multiple ways. For example, “Meir Hoffman” produced no results in the basic search engine, but using the advanced search option with a “sounds like” function, the records of “Mejer Hofman” appeared. Advanced search options also include the ability to search by town of origin, age at arrival, and the name of the ship on which immigrants traveled. A researcher with patience and perseverance can likely find the correct individual.

While the site tries to provide orderly access to a multitude of documents, disorder and frustration reign. Jewish passengers prove particularly difficult to locate via the search engines due to the frequent interchanging of Yiddish, Hebrew, or Anglicized versions of both first and surnames. The site provides basic tips for assisting in difficult searches, but new or inexperienced researchers will likely find these resources neither obviously located nor easily accessible. Users of the “sounds like” function mentioned above would benefit from an explanation of how this feature works and suggestions of how best to enter information to simplify searches.

Despite these technical issues with the AFIHC’s site design, it should be noted that much of the search frustration results from the confusion that surrounded the actual immigrant experience and the chaos that ensued when Ellis Island officials tried to document and process the millions of individuals arriving in America. The fact that researchers can view these valuable historical documents from any location and do so through high-resolution scanning makes this database a valuable resource for both professional researchers and other interested site visitors.

Hasia Diner and Shira Kohn

New York University

New York, New York