talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

African-American Sheet Music, 1850–1920

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/award97/rpbhtml/aasmhome.html

Created by Brown University Library and the National Digital Library Project, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Reviewed June 4–18, 2001.

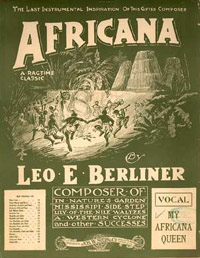

This digital collection of song sheets has been selected from the approximately 500,000 pieces of music housed at the John Hay Library at Brown University. Roughly 6,000 items fall into the African Americana category, and of that number 1,305 are digitized at this site. The average length of each piece of sheet music is five or six pages, and the site does a remarkable job of clearly reproducing cover images, lyrics, and music for easy navigation and printing. The music spans the era from antebellum blackface minstrelsy through the Civil War and into the early twentieth century. The era is, of course, incredibly consequential in African American history, and this collection provides a valuable resource toward understanding the complex relationship between commercial culture and race politics. The site presents a wealth of primary source material about the rise of popular song, the burgeoning American entertainment industry, the centrality of racism to commercial culture, and the African American struggle to produce art in this milieu.

The home page introduces the collection with the images and names of prominent black artists of the era including Bob Cole, Aida Overton Walker, and James Reese Europe. Undoubtedly, one of the most exciting aspects of the collection is that it makes the work of these artists widely available—artists who were representative of a generation of African American composers and performers who spearheaded black musical comedy at the turn of the century. Unfortunately, their songs do not adequately represent the plethora of “African Americana” songs of the era. A subject search for “Afro-American composers” yielded only 95 song sheets. White composers wrote most of the songs presented, and white publishers produced almost all of the pieces, even those authored by African Americans. Accordingly, most song references to black life incorporated stereotypes that reflected and reinforced American racism.

Not everyone who accesses this site may be familiar with the proliferation of white-determined images of blackness on the antebellum minstrel stage and in the post-Reconstruction “coon song” era. If users do not consult any of the books listed on the site’s extensive bibliography, they learn from the online introduction only that the period includes “rags and so-called ‘coon’ songs, whose strident racial images have lost none of their power to shock.” The need to provide a more detailed context for the sheet music becomes even more evident when searching the site. The site’s subject heading “Black nationalism” brought up one song sheet, “Every Race Has a Flag but a Coon”—a song that when performed had been applauded by whites and denounced by blacks. A keyword search for “watermelon” elicited a list of songs that were categorized under subheadings of “Afro-Americans-songs and music” or “Afro-Americans-social life and custom,” but with no explanation of watermelon’s prevalence as racist stereotype. Searching for keywords “stereotype” and “racism” brought no records.

This online archive is a valuable resource and meets vast public interest; it is easily navigated and is readily accessed through Internet searches for “African American music.” Fortunately, the site’s “learning page” does announce that it will be updated with more information. All users, but particularly those who happen upon the site with little prior knowledge, would benefit from a more detailed online introduction to the collection, one that better emphasizes how the sheet music business was tied to the rise of an entertainment industry saturated with American racism.

Karen Sotiropoulos

Cleveland State University

Cleveland, Ohio