talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

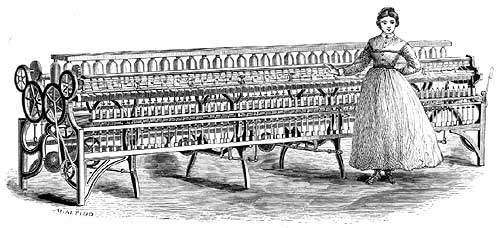

The latest model.

In the 1820s, operatives in the Lowell cotton mills, mostly women, worked twelve hours a day, six days a week. Holidays were few and short: July Fourth, Thanksgiving, and the first day of spring. In the 1830s, with increased competition, conditions worsened as owners cut wages, raised boarding house rents, or increased workloads. To protest these changes, women went out on strike in 1834 and 1836. This promotional engraving showed a mill woman standing in unlikely repose beside a Fale and Jenks spinning frame. The benign relationship of the figure to the machine may have served to reassure nineteenth-century observers that factory work would not debase “virtuous womanhood.”

Source: James Geldard, Hand-book on Cotton Manufacture . . . (New York, 1867).