talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

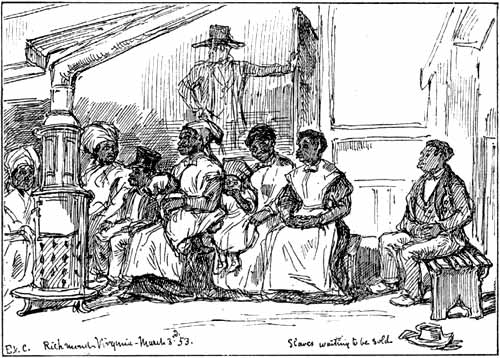

In the Richmond Slave Market

In 1852–53, the popular British writer William Makepeace Thackeray toured the United States. While he lectured to enthralled American audiences, his secretary Eyre Crowe meticulously recorded the trip in words and pictures. Crowe, who studied painting in France, later published an illustrated memoir of the U.S. trip called With Thackeray in America. Crowe included in his account a visit to the Richmond, Virginia, slave market where he witnessed and sketched a slave auction. As this excerpt demonstrates, his simple act of drawing the harsh circumstances of the slave trade was viewed by the auctioneer and planters as a threat. After his return to England, Crowe turned his sketches into a series of paintings that starkly depicted the auction and the subsequent forced separation of family members and friends.

The 3rd of March, 1853, is a date well imprinted on my memory. I was sitting at an early table d’hote breakfast by myself, reading the ably conducted local newspaper, of which our kind friend was the editor. It was not, however, the leaders or politics which attracted my eye, so much as the advertisement columns, containing the announcements of slave sales, some of which were to take place that morning in Wall Street, close at hand, at eleven o’clock.

Ideas of a possibly dramatic subject for pictorial illustration flitted across my mind; so, with small notepaper and pencil, I went thither, inquiring my way to the auction rooms. They consisted, I soon discovered, of low rooms, roughly white-washed, with worn and dirty flooring, open, as to doors and windows, to the street, which they lined in succession. The buyers clustered first in one dealer’s premises, then moved on in a body to the next store, till the whole of the tenants of these separate apartments were disposed of. The sale was announced by hanging out a small red flag on a pole from the doorway. On each of these was pinned a manuscript notice of the lot to be sold. Thus I read:—“Fifteen likely negroes to be disposed of between half-past nine and twelve—five men, six women, two boys, and two girls.” Then followed the dealer’s signature, which corresponded to that inscribed over the doorway. When I got into the room I noticed, hanging on the wall, a quaintly framed and dirty lithograph, representing two horsemen galloping upon sorry nags, one of the latter casting its shoe, and his companion having a bandaged greasy fetlock; the marginal inscription on the border was to this effect:—“Beware of what you are about.” I have often thought since how foolish it was, on my part, not to have obeyed this premonitory injunction to act prudently in such a place as this was. The ordeal gone through by the several negroes began by making a stalwart hand pace up and down the compartment, as would be done with a horse, to note his action. This proving satisfactory, some doubt was expressed as to his ocular soundness. This was met by one gentleman unceremoniously fixing one of his thumbs into the socket of the supposed valid eye, holding up a hair by his other hand, and asking the negro to state what was the object held up before him. He was evidently nonplussed, and in pain at the operation, and he went down in the bidding at once. More hands were put up; but by this time feeling a wish for fresh air, I walked out, passing intervening stores and the grouped expectant negroes there.

I got to the last and largest end store, and thinking the sales would occupy a certain time, I thought it might be possible to sketch some of the picturesque figures awaiting their turn. I did so. On rough benches were sitting, huddled close together, neatly dressed in grey, young negro girls with white collars fastened by scarlet bows, and in white aprons. The form of a woman clasping her infant, ever touching, seemed the more so here. There was a muscular field-labourer sitting apart; a rusty old stove filled up another space. Having rapidly sketched these features, I had not time to put my outline away before the whole group of buyers and dealers were in the compartment. I thought the best plan was to go on unconcernedly; but, perceiving me so engaged, no one would bid. The auctioneer, who had mounted his table, came down and asked me whether, “if I had a business store, and someone came in and interrupted my trading, I should like it.” This was unanswerable; I got up with the intention of leaving quietly, but, feeling this would savour of flight, I turned round to the now evidently angry crowd of dealers, and said, “You may turn me away, but I can recollect all I have seen.” I lingered in a neighbouring vacated store, to give myself the attitude of leisurely retreat, and I left this stifling atmosphere of human traffic. “Crowe has been very imprudent,” Thackeray wrote to a friend afterwards. And, in truth, I soon reflected it was so. It might have led to unpleasant results to the lecturer himself, bound, as he went South, not to be embroiled in any untoward accident involving interference with the question of slavery, then at fever-heat, owing to Mrs. Stowe’s fiery denunciations in “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Though I have no real ground for the assumption, it has often occurred to me that the incident was allowed to drop quietly, owing to the timely intervention of friends, who threw oil upon these troubled waters, and buried their wrath in oblivion.

The narrative here given is so simple as to bear the stamp of truth which needs no further corroboration. Still, by way of amplification of scenes subsequent to my withdrawal—or flight, if the reader prefers, though I was not sensible of it—I herewith given the account, which I found published exactly a week after in the

Extract of part of a letter in the New York Daily Tribune of March 10th, 1853, written by a New Yorker on Southern tour. The letter is dated "Richmond, Va., Thursday, March 3rd, 1853:—

[After describing the previous sales, he comes to the last one.]

After these sales we saw the usual exodus of negro slaves, marched under escort of their new owners across the town to the railway station, where they took places, and “went South.” They held scanty bundles of clothing, their only possession. These were the scenes which in a very short number of years made one realise the sources of the fiercest of civil wars, and which had their climax when General Grant mustered his forces upon this spot as a centre against the equally gallant General Lee.

Source: Eyre Crowe, With Thackeray in America (London: Cassell and Co., 1893), 130–136.

"A scene occurred in this room which ‘may yet be heard from.’ Just before the sale commenced, a young well-dressed gentleman entered the room—placing himself in one corner of the room—began to take a sketch, and had proceeded quite far before he was noticed by anyone but myself. At last he attracted the attention of some of the bystanders, until full twenty or more were looking over his shoulder. They all seemed pleased with what he was doing, as long as the sketch was a mere outline, but as he began to finish up the picture, and form his groups of figures, they began to see what he was about, and then someone went up privately to the auctioneer (who had by this time got one or two sold), and informed him what the man was doing. He came down from the stand, went and overlooked what he was doing for a moment, and saw himself written down for the first time in his life. He inquired of the man what he was doing. The answer was ‘I do not know that I am bound to answer your inquiry.’ Mr. Auctioneer took his stand again, but was evidently so enraged that he could not go on, for by this time the whole company was aware of what was being done. And some proclaimed with a loud oath that the likeness was ‘d——d fine,’ ‘most splendid;’ others were for ‘footing’ him. The artist took the hint, however, without the kick, and left the room. But now we had a specimen of Southern bravery. They were all sure that he was an Abolitionist, and they all wanted to ‘lend a foot’ to kick him, while one small gentleman said he would pay twenty-five dollars to hire a negro to do it. The excitement soon passed over; not, however, without leaving on my mind the truth of the maxim that ‘He who fights and runs away, may live to fight another day.’"