talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

How A Battle Is Sketched

In this article, written 24 years after the war for the children’s magazine St. Nicholas, former Harper’s Weekly sketch-artist Theodore R. Davis recollects the hazardous and inventive ways that pictorial journalists reported the Civil War. While photography was still in its infancy—unable yet to capture action or to be cheaply reproduced in periodicals or books—artists' battlefront sketches were the public’s primary source of visual news of the war’s people, places and events. Davis, who was 21 at the start of the war, was typical of this new type of reporter, recording direct observations or collected stories in rough sketches and notes that were dispatched to newspaper offices in New York where they were made into wood engravings and printed as illustrations in publications such as Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, and the New York Illustrated News (the South had no comparable pictorial news resource).

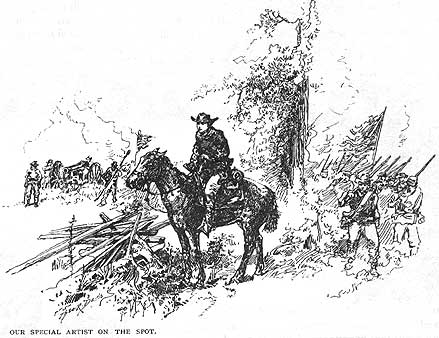

The method of sketching a battle by “our special artist on the spot” is not known to most persons, and droll questions about such work are asked me by all sorts of people. Most of them seem to have an idea that all battlefields have some elevated spot upon which the general is located, and that from this spot the commander can see his troops, direct all their maneuvers and courteously furnish special artists an opportunity of sketching the scene. This would, of course, be convenient, but it very seldom happens to be the case; for a large army usually covers a wide extent of country,—wider in fact than could possibly be seen, even with the best field-glass, from any situation less elevated than a balloon high in air. A battle is usually fought upon a pre-arranged plan, but most of the circumstances and actors during the actual conflict are unseen by the chief general. He, however, mentally comprehends everything and readily understands what is going on from the reports which are constantly brought to him by staff-officers. It may happen that the point where the most important movement is to be made, is so located that no general view of it can be had, and it is only by going over the actual ground that one can observe what is going on. Now, the artist must see the scene, or object, which he is to sketch, and so, during the battle, is obliged to visit every accessible point which seems likely to be an important one, and there make a sufficient memorandum, or gain such information as will enable him to decide at the close of the action precisely what were its most interesting features. Many persons have said that since my duty was only to see, and not to fight, they should think that I would not be shot at, and so did not incur much danger of being hit. Ordinarily, of course, the fact is that, in a general engagement, special individuals who do not seem to be prominent are seldom selected as targets, but if your own chance is no worse, it is surely no better than that of others near you. To really see a battle, however, one must accept the most dangerous situations, for in most cases this can not possibly be avoided. There have been occasions when some industrious sharp-shooter troubled me by a too personal direction of his bullets. No doubt the man regarded me as somebody on the other side, and considered he was there to shoot at anything or anybody on the other side. My most peculiar experience of this sort was having a sketch-book shot out of my hand and sent whirling over my shoulder. At another time, one chilly night after the day of a hard battle, as I lay shivering on the ground with a single blanket over me, a forlorn soldier begged and received a share of the blanket. I awoke at daybreak to find the soldier dead, and from the wound it was plain that but for the intervention of his head the bullet would have gone through my own. There are also incidents which would show the other risks, besides those during a battle, to which a special artist is exposed. But it is the work and not the adventures of the artist which I shall describe; and to make the subject clear it will be well to explain how much there was to be learned when I first entered the field as a campaign artist.

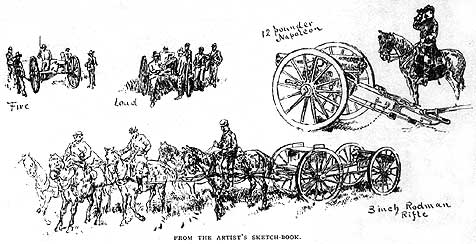

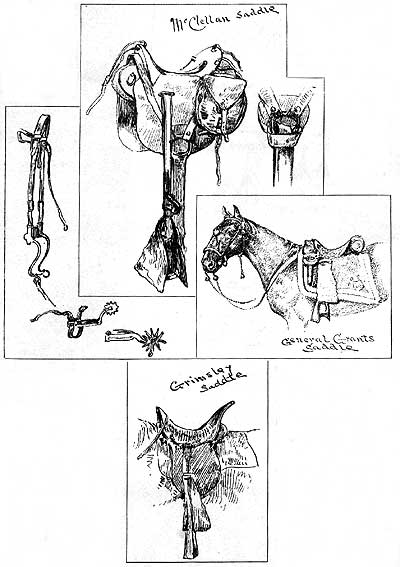

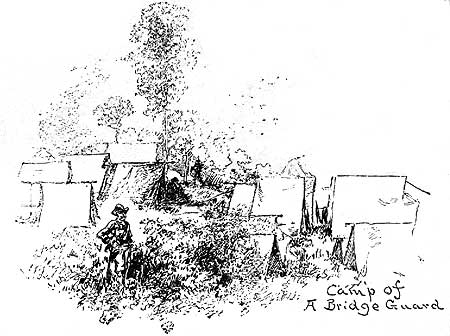

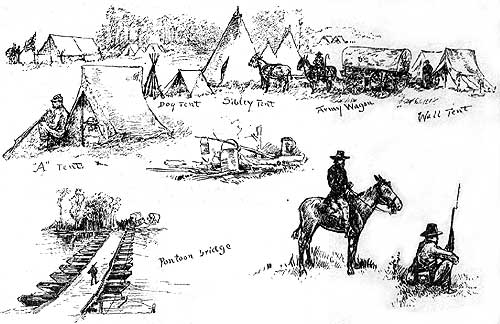

Infantry, cavalry, and artillery soldiers, each had their particular uniform, and besides these, their equipments, such as belts, swords, guns, cartridge-boxes, and many other things, were different. Their tactics and maneuvers were not alike, and some distinguishing point in each uniform designated the corporals, sergeants, lieutenants, captains, majors, colonels, and generals. As many as ten different saddles were in use, and of the army homes—tents—there was a great variety. The harness for artillery horses was peculiar, as was that of the mules which drew the army wagons and ambulances. Now, these are only some of the things,—a few of them,—but sufficient to show the necessity for a special sketch-book, in which to make, whenever I found an opportunity, memorandum sketches of every new thing. I thus provided myself with a reference book for use when active campaigning commenced; for then there would be no time to secure detailed sketches, and under some circumstances it would often be impossible to get more than a very rough sketch from which to finish a drawing of some very important occurrence. Some leaves taken from one of these reference note-books are shown here, to explain what these memoranda were like. They are somewhat smaller than the originals, but it should be mentioned that these note-books were small, so that they might conveniently be carried in my pocket, ready for use at any moment.

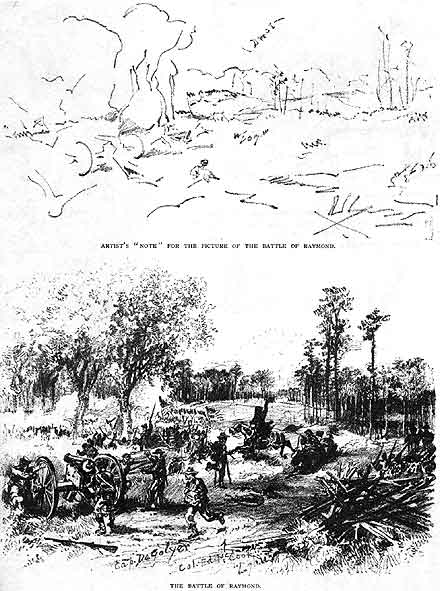

Now, a word about my army homes: There never was the slightest difficulty in finding quarters, and, when with the Western army, I sometimes had several different quarters at the same time, places where I paid a regular monthly mess-bill, whether present or absent, and thus was enabled to stay over night at the place nearest to the scene of the next day’s work, or could immediately commence to prepare the finished drawings to be sent away to my journal at the very earnest opportunity. Of course the character of these drawings varied both according to the circumstances under which they were made and the time afforded for their elaboration from the sketches. And the sketches, or mere notes, as at times they were, might sometimes be absolutely unintelligible except to myself (although even now, and after twenty-five years have passed, many of these same rough notes bring back to my mind the scenes they indicate, and suggest many forgotten details). Probably my note-book of General Grant’s Vicksburg campaign contains some of the very queerest specimens of hasty memoranda, and one of these (which it will be observed bears every evidence of being made on the spot) shows a locality in which bullets flew thick and fast, and everybody was quite busy and active.

The place was the scene of a part of the battle of Raymond, and the note will no doubt amuse most of those who see it; but, should it meet the eye of any of the veterans of the Vicksburg campaign who were in the Raymond fight, they will not, remembering the experience, wonder at the appearance of the memorandum. My horse had been shot a few moments before the sketch was made, and there is still a reminder of the incident in the form of a scar on my left knee as large as a half-dollar, made by the bullet that killed my horse-or some other bullet. The Raymond fight was not a great battle, but one of those compact and vigorous engagements at close quarters, without any protecting earthworks. Under such conditions it could last but a brief time before one side or the other gave way, and that time it was the Confederate soldiers who found the situation too uncomfortable to remain; and as we followed quickly after them, and camped some miles beyond the scene of the battle, what I saw of the field I saw during the action.

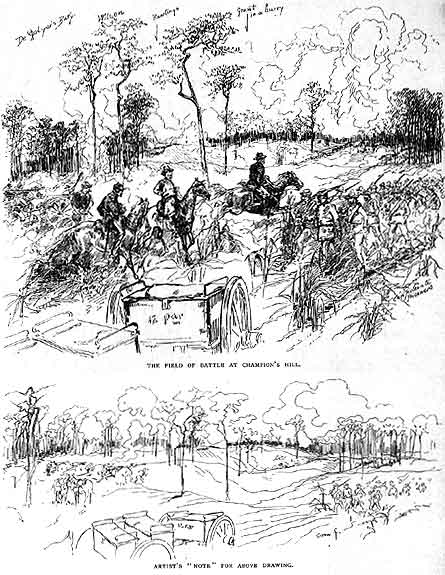

By comparing the note with the drawing, a something may be discovered which stands for one of Captain De Golyer’s six-pounder cannon.* [* Illustrating the chances of war—when the paper containing the illustrations of the Vicksburg campaign reached me, a copy was handed to Captain De Golyer, who at that moment was with his battery in the advance line in front of Vicksburg. The captain started for his tent, at some distance in the rear, and in a place of comparative safety, and while there, looking over the paper, a chance bullet struck him, inflicting a wound which caused his death a few weeks afterward.] The written word, “Logan,” means General Logan; “Mc” is for Colonel Ed. McCook, who was at the moment limping away, wounded, and had taken two muskets for crutches; “M" shows where General McPherson was, and near him was the brave Lieutenant-Colonel W. E. Strong, who a year afterward rescued General McPherson’s lifeless body from the battlefield of Atlanta. Trees and smoke are suggested, and a few marks (which might mean anything) stand for the road and a bit of destroyed fence. The word ”dust“ shows where there was a dust cloud—an evidence of a movement of troops. The name of the division which was marching there, I took pains to learn afterward. There was an incident in this scene which was as amusing as it was characteristic of the chief actor, Captain Tresalian, an Irish officer on the staff of General Logan. He was seated astride of the top-most rail of the fence, across which, in some places, the fight was going on with clubbed muskets; which side the captain was most interested in was doubt-ful, for, with cap in one hand and sword in the other, he was encouraging both parties to go in, and do their best, while he occupied a reserved seat, a most interested spectator. This man was a type of the soldier who loves a fight, and true stories of some of his doings seem almost too improbable to believe. I think he was unconscious of danger, and I know that I was not, for in some of my sketch-books there are memorandum sketches of some battlefield occurrences which show plainly that the hand holding the pencil was unsteady; and jerky marks here and there make it pretty plain that the locality was an unsafe one. The surroundings, as well as the danger, had some influence at the moment when such sketches were made; for most of these ”Get-out-of-that“ sketches, as my army friends called them, show simply the locality of some exciting incident, and not a general view, such as that of the field at Champion’s Hill (or Baker’s Creek, as the Confederate soldiers called the battle). The memorandum sketch of that action shows a general view of the field, indicated with reasonable distinctness—even if ”corn f" does stand for a field of corn! After leaving the spot, I saw General Grant and some of his staff at that point, and so introduced them in the sketch, to add interest to the scene. Of a number of sketches made during this battle, only one or two were finished to send to the paper, for during the Vicksburg campaign the movements and incidents occurred so rapidly that it was difficult to decide what to spare time for, so as to send sketches which would give the best general idea of what had happened.

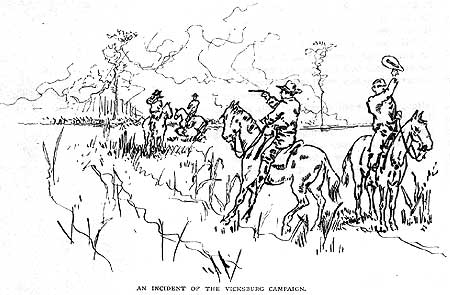

An incident which is worth telling took place after the close of the battle of Champion’s Hill. The Confederates had started back to Vicksburg, and some of our troops marched hastily in the same direction; clouds of dust rose. from beyond the forest to the left of the road along which we marched, and we were not surprised, upon coming to a large field, to see soldiers marching along a road on the opposite side, nor astonished to see two mounted men leave the column and ride toward two of our officers who had immediately started to ascertain what troops those were. When, presently, we saw these horsemen firing their revolvers at one another, we knew that those were not our troops marching over there, and made arrangements accordingly.

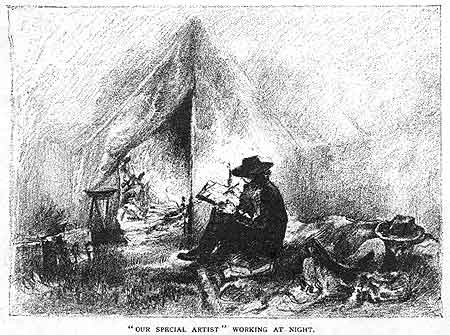

Some time after the close of the war, two gentlemen met on a steamboat in the South, and each thought that he recognized the other, though where they had met neither could then recollect; but it soon came out that it was on that 16th of May, 1863, after the Champion’s Hill engagement, and as they shook hands for the first time each was glad that his pistol-shot had done the other no harm. A glance at the illustration of “our special artist” working late at night to finish his sketches, makes me tired enough to stop right here; for it brings to mind the many nights, when a few hours' sleep was all the rest the Special could expect to have after a long day, during which nearly every part of an army covering miles of country had been visited and the general situation of the forces had been ascertained.

Of the different ways of forwarding sketches, the mail, next to a special messenger, was found to be the quickest and safest; and now, looking back at the prodigious work that was accomplished by those whose duty it was to forward and receive our army’s mail, I know of nothing else wherein the Government’s care of the soldiers was more fully displayed. In closing this article, it ought to be stated that I have made sketches upon many battle-fields where the fighting was too extended for any single per-son to hope to reach more than a few of the most prominent points, and I have found that a sure guide to these points was to go toward the place where the heaviest musketry fire was heard,—not a pleasant thing to do, but quite in the line of duty for one who is "special artist on the spot."

Source: Theodore R. Davis, St. Nicholas, 16 (July 1889): 661–68.