talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

Bob Hope and American Variety

http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/bobhope/

Created and maintained by the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Reviewed Oct. 3–4, 2006.

For over half a century, Bob Hope was one of the most familiar entertainers in the United States. Before his death in 2003, he and his family donated many of his personal papers, as well as materials related to his radio and television programs, to the Library of Congress. An endowment helped create the Bob Hope Gallery of American Entertainment. The result is a fine exhibition that uses the Hope collection and materials from additional archives; general audiences should find it informative and interesting.

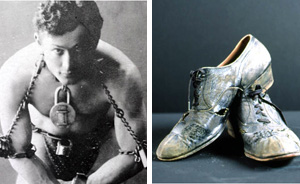

Harry Houdini, ca. 1899; Eddie Foy’s dancing shoes, ca. 1910

A strength of the exhibit is its explanation of how Hope reflected larger trends in American entertainment. Vaudeville was especially important. It was exceedingly popular at the turn of the century, and it was from vaudeville’s stages that Hope and many other performers launched their careers. The exhibit includes approximately 350 well-chosen images, and it is divided into ten sections, ranging from a short sketch of Hope’s early life to others that show his relationship with major entertainment forms that drew on the variety format.

The exhibit understandably pays the greatest amount of attention to vaudeville (it is the subject of three sections and almost 150 images) and conveys a sense of its rich heritage and influence. Short descriptions emphasize the dominant role of ethnicity among performers and acts. The caricatures of different immigrant and racial groups were often offensive but at the same time “provided a means of assimilation for members of the audience by allowing them to laugh at other ethnic groups, ‘outsiders.’” Some of the exhibit’s images and commentary deal with the importance of Tin Pan Alley as well as performers such as Bert Williams, Harry Houdini, and Eddie Foy.

With vaudeville’s fading in the early 1930s, Hope, along with a number of other entertainers, brought their stage training to movies and radio. The exhibit’s sections on motion pictures and radio note larger developments in those media—for example, the coming of sound to the movies and the development of NBC’s Blue and Red radio networks. A Hope quotation neatly characterizes early TV: “When vaudeville died, television was the box they put it in.”

The exhibit provides a commendable range of images. There are photos not just of Hope but of performers such as Eva Tanguay, Trixie Friganza, Eddie Cantor, and Johnny Carson. Other images include sheet music covers, snippets from jokes and monologues, movie posters, magazine covers, newspaper headlines, fan mail, and television scripts. The exhibit is easy to access. While it reflects scholarly interpretations, its main appeal should be to a broad public audience who can enjoy it and learn about not only Bob Hope but also the larger contours of American entertainment.

Hope’s charm rested largely on the popular persona that he developed: “brash, yet not too serious about himself, and a comic wiseacre who endeared himself to his audience by taking them into his confidence.” The exhibit might have also noted that Hope was an establishment entertainer, whose comedic style was safe and innocuous. He “rubbed but did not scratch,” as one person observed.

LeRoy Ashby

Washington State University

Pullman, Washington