talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

Nineteenth-Century American Children and What They Read

http://www.merrycoz.org/kids.htm

Created and maintained by Pat Pflieger, West Chester University, P.A.

Reviewed Aug. 23, 2005.

Children in Urban America Project

http://www.marquette.edu/cuap/

Directed by James Marten and Karen Kehoe, Marquette University.

Reviewed Aug. 23, 2005.

Children in the twenty-first century are technologically savvy. They are comfortable surfing the Web, instant messaging with friends (e-mail is for old people), listening to music, and doing their homework on computers—often all at the same time. But what records will they leave behind for future historians? Perhaps a few old-fashioned e-mails, compact discs (CDs), and digital video discs (DVDs). But most of the Web sites they visit and instant messages they send will disappear. These two Web sites attempt to understand the lives of young people in the last two centuries through a host of materials that did survive—writings by and for children, drawings, photographs, and writings about children.

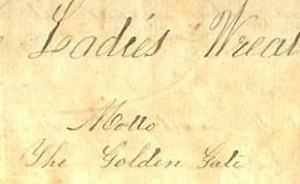

Some young authors created their own magazines. The “The Ladies Wreath,” apparently “published”

in the 1850s, includes jokes, an essay on smoking, poems on death — and some truly creative spelling.

Nineteenth-Century American Children and What They Read is a Web site born of a passion for exactly that—material written for children, and occasionally by children, in the nineteenth century. Pat Pflieger, an English professor and the site creator, is interested in popular books and magazines that are not well known today. Topics range from morality tales to slavery to the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. An 1857 poem by William C. Cutter entitled “Skating—Woman’s Rights” asks why a woman may not skate when “She can walk, and run, and ride.” Fear of revealed ankles is not enough to persuade the author that women should not partake of the newest fad.

Drawing on that passion, Pflieger has purchased, transcribed, and made public a significant number of primary sources, as well as bibliographies and scholarly works. The section called “Children” provides an eclectic sampling of materials from letters, adoption notices, and articles about raising children to writings by children, including scrapbooks, exercise books, letters, and a diary. There is no clear rationale for the inclusion of items beyond availability.

“Magazines” offers more than two hundred transcribed articles, jokes, letters, and illustrations from twelve magazines, as well as a “small gallery” of magazine covers. “Some of their books” provides complete transcriptions for twenty-seven books for children as well as articles and reviews of the books and of children’s reading by nineteenth-century adults. In addition, the site makes available seven scholarly essays by Pflieger and comprehensive bibliographies on social history, children and child rearing, reading in the nineteenth century, Samuel G. Goodrich, and the children’s author Jacob Abbott. Pflieger annotates many of the materials, providing historical context (sometimes very brief ) and bibliographic information (usually). Text is almost always transcribed, and Pflieger is forthcoming about omissions and possible errors. Unfortunately, originals of the materials are generally not available.

Despite the eclectic nature of the site, Pflieger has created a wonderful resource for teachers, students, and researchers interested in children, publishing, or literacy in the nineteenth century. Navigating the Web site requires patience, however. First created in 1999, the Web site has grown without a cohesive structure or search engine. All materials are included on the three comprehensive indexes: title, subject, or date. Clicking on an item from the index sometimes leads you to the top of a browse page where you must search for a link to the item. Other times, you move directly to the location on the browse page that links to the item. Occasionally you move directly to the item itself.

“Scene from a toy loan center administered by the federal and county governments in the 1930s”

More narrowly defined geographically but not chronologically, the Children in Urban America Project (CUAP) focuses on children and childhood in urban America, specifically in the greater Milwaukee area, from 1850 to 2000. The site is organized around five sections, four “central experiences in children’s lives”—Work, Play and Leisure, Schooling, and Health and Welfare—and a final section entitled “Through Children’s Eyes” that offers stories, oral histories, and memoirs of children who grew up in Milwaukee. Each section offers a brief introduction of the topic (such as schooling in Milwaukee), a limited gallery of images, and a series of “Special Topics” combining a background essay and relevant primary sources. Topics range from the Socialist party, religion, and newsboys to poliomyelitis in Milwaukee County. While limited, these could be very useful for teaching. They bring together relevant primary sources, frame the topic, and offer suggested keywords and search terms for locating additional resources.

The archive offers more than four thousand resources, including newspaper stories, photographs, quantitative data, oral histories, personal narratives, and summaries of various topics and time periods. At first glance, it is not apparent that the site offers such a wealth of resources, and without using the search page it can be difficult to access many of these. On some pages, the search is only accessible by clicking on a purple kite in the top right corner labeled “Search CUAP.” On other pages, “Search entire site” in the footer is the only link to the search page. Once you reach the search page, though, you can easily search for a word or phrase or can select one of the predefined keywords such as addiction, adoption, dance, or protest. You can narrow the search by selecting more than one keyword, limiting the search results to one of the five sections of the site (for example, Health and Welfare), selecting one of ten neighborhoods, or choosing a decade. A search on “curriculum” returns close to 200 results, but “curriculum” and “sexuality” narrows it to 6.

Another useful feature of the site offers research topics and tips. Questions are grouped into middle school, high school, and college levels and cover a host of subjects, from games to newspaper coverage of children to the impact of technology on the lives of children. While CUAP is limited in scope geographically and would benefit from clearer navigation and either expansion of the current sections or a stronger focus on the search as a central feature of the site, the site as a whole offers a compelling look at children during an important time in the history of childhood.

Taken together, these Web sites provide important primary sources and ideas for studying the history of children, a rapidly growing field and a topic that young people often find fascinating. The Web sites are rich if slightly quirky; they will help the field continue to grow by allowing for deeper examination of the institutions that shaped children’s lives and the voices of children as they read, wrote, and grew.

Kelly Schrum

George Mason University

Fairfax, Virginia