talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

The Walt Whitman Archive

http://www.whitmanarchive.org/

Edited by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price. Maintained by the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities, University of Nebraska.

Reviewed May 2012.

“I am large, I contain multitudes,” wrote Walt Whitman in his poem “Song of Myself” (1855). It is a statement with which anyone who has studied this great and protean poet can easily agree. Whitman (1919–1892) has fascinated generations of historians, his long life and large body of work intimately connecting with every important event and movement in the nineteenth-century United States. His poetry is an invaluable resource but also an exceptionally tricky one: his masterpiece Leaves of Grass, in which “Song of Myself” originally appeared, was released in multiple editions over his lifetime, growing and changing with every iteration. The poem that a historian quotes may be very different from the poem read by Whitman’s contemporaries.

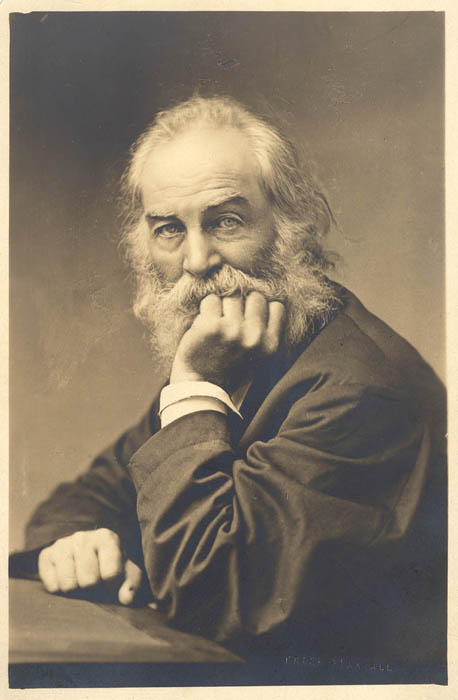

G. Frank Pearsall, Photographic portrait of Whitman, ca. 1870

For decades, only specialists with easy access to rare book collections could confidently navigate their way among Whitman’s textual intricacies. Since 1995, however, the Walt Whitman Archive, an ongoing project edited by two of the nation’s most prominent Whitman scholars (Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price), has made a vast range of texts and interpretive material available to researchers, teachers, and students. At the heart of this elegantly designed archive are the seven principal editions of Leaves of Grass, ranging from 1855 to 1891–1892, presented as both page images and as searchable text, with each edition linked to a helpful introduction taken from Walt Whitman: An Encyclopedia (edited by J. R. LeMaster and Donald D. Cummings, 1998).

The archive includes the original appearance of all Whitman poems that were published in periodicals; in every case the full page is included so that the poem can be seen in its journalistic context. There is also an in-progress section on Whitman’s extensive journalism; the site editors have begun with his Civil War journalism and have included the entire run of the New York Aurora during the three months of 1842 that Whitman edited the newspaper.

The archive’s most dazzling section—in its visual impact and its possibilities for research—is a collection of Whitman manuscripts. The goal is eventually to include all 70,000 known manuscripts. For now, the Web site includes poem manuscripts and three Civil War notebooks, plus nearly 2,000 documents that Whitman produced while working as a clerk in the attorney general’s office in Washington, D.C., from 1865 to 1873. Price, who discovered the documents in a National Archives annex in Maryland, is putting them online as page images with transcriptions, wisely leaving the annotations to follow. It remains to be seen what uses imaginative scholars will make of this trove of material.

Other particularly valuable aspects of the archive include the nine volumes of Horace Traubel’s With Walt Whitman in Camden (1906–1996), a two-million-word record of the last four years of Whitman’s life. The archive is compiling Whitman’s incoming and outgoing correspondence; so far the collection covers 1860 to 1873. A bibliography of secondary works about Whitman includes virtually everything published from the nineteenth century to today, with most entries briefly annotated.

There is much more on this site to reward the curious: teaching aids, biographical material, photographs, and even Whitman’s voice—recorded in 1889 or 1890 on an Edison wax cylinder—reciting the opening lines of his poem “America” (1888). The Walt Whitman Archive, arguably the most ambitious scholarly single-author site on the Internet, is an essential resource for anyone teaching and writing about nineteenth-century America.

Michael Robertson

College of New Jersey

Ewing, New Jersey