talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

In Motion: The African-American Migration Experience

http://www.inmotionaame.org/home.cfm

Created and maintained by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York, N.Y.

Reviewed Dec. 4–12, 2005.

Movement and mobility—forced, voluntary, and something in-between—have been enduring characteristics of African-American life. On the website In Motion, those activities are divided into thirteen categories. One set of categories explores movement in colonial North America and the United States: runaway journeys; domestic slave trade; western migration; northern migration; the Great Migration; the second Great Migration; and migration back to the South. Another set explores movement through the Atlantic world, beginning with the transatlantic slave trade: colonization and emigration; and immigration from Haiti, the Caribbean, and Africa.

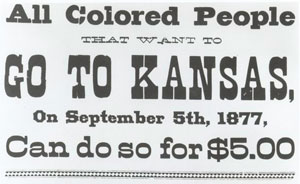

Advertising poster intended to attract African American homesteaders to Kansas.

There are over 16,500 pages of texts, 8,300 illustrations, and 67 maps on the site. One of the strengths of this impressive site is that it pays attention not only to well-known African-American “motions,” such as the transatlantic slave trade and the Great Migration, but it also includes material from lesser-known migrations. Material in the "Colonization and Emigration" category, for instance, covers Africa, Haiti, and Canada, as well as efforts to emigrate to Trinidad and Mexico.

Each of the thirteen categories is separated into texts, images and maps, but navigation bars on all pages enable users to jump between the three types of material at any time. Included in the texts are essays written for the site by scholars prominent in the field. Each category is also divided into several topics.

For example, in the category "The Western Migration,“ there are nine topics, a bibliography, and links to other Web sites. To narrow this example further, one of the nine topics, ”To Kansas," has a narrative of roughly nine hundred words, which is interspersed with links to primary sources including memoirs, interviews, Senate testimony, a government report, and two Journal of Negro History articles from 1936 and 1948. There are also four recent articles and book chapters on the topic by historians. “To Kansas” alone includes sixteen images with bibliographic data. Five maps are included in the category of “Western Migration,” and each has annotation on more specific topics.

Each of the Web site’s texts can be read as a PDF (portable document format)—an invaluable option for the primary sources—or as text that can be searched by word (though this function was not working very well during the week or so I reviewed the site). Users may also read sources in both formats at once.

The website also includes extensive lesson plans for middle and high school teachers, arranged by discipline as well as by topic. Each plan has an overview and a description of the national curriculum criteria that the lesson meets. The plans lay out clearly the material needed, how to begin the class, procedures to follow, and questions to ask. Their great strength is that they have the students interpret the past using primary sources of all types.

In Motion could be made even better with a few thematic essays exploring the links and differences between motion at different times and different places. An essay on gender and movement, for instance, would be a useful way to make connections between the thirteen categories on which the website is based. Regardless, this is a remarkable website that will prove useful to researchers, teachers, and students in both schools and universities.

Clare Corbould

University of Sydney

Sydney, Australia