talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum

http://www.rockhall.com/

Created and Maintained by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Cleveland, Ohio

Reviewed October 2004.

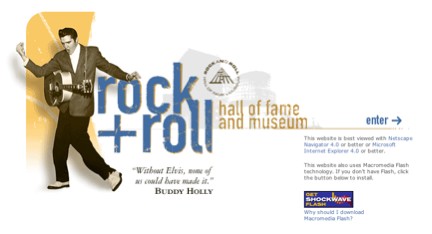

The Rock and Roll Hall of fame in Cleveland walks the tired path of celebrity nostalgia. The opening screen, predictably an image of Elvis Presley, establishes that the museum celebrates performers and celebrity, not audience; rock and roll as hero worship, not as community or as a dialogue between audience and performer, music company and store owner, critic and fan. A quote from Buddy Holly cements this approach: “without Elvis,” says Holly, “none of us could have made it.” Who is “us?” Other performers? Or a generation of listeners? If the latter, why have Holly as the speaker?

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Splash Screen

On the main screen, each day brings a featured member of the hall of fame, as well as a scrolling link to a rotating series of inductees and links to ongoing exhibits and general museum information. But the site contains little archival depth—nearly all links lead only to brief biographical entries on individual hall of famers.

Here again celebrity rules. For example, Leadbelly, who the museum commemorates because he “influenced” many other celebrity performers; the entry hints at a troubled relationship between Leadbelly and the Lomaxes, but gives no details. Alan Lomax’s promotion/exploitation of Leadbelly makes a fascinating and revealing story, which speaks volumes about genre, race and marketing, but the museum glosses over this to largely conclude that Leadbelly is important because he influenced Led Zeppelin’s Robert Plant.

The museum’s entries on other hall inductees are similarly light, mentioning “controversy” without giving any but the most general terms; the entry on Chuck Berry never notes his imprisonment in the late 50s and early 60s, the entry on Alan Freed mentions a scandal involving “payola” but offers little more.

Aside from an obscure shockwave program which lets users construct a simple blues form (which did not work), the site offers no samples of the actual music, and no lyrics: instead, it presents changing images of celebrity relics: Hank Williams' hat, Neil Young’s jacket. etc. Clicking on these links takes users not to a discussion of the artifact but—again—to the relevant performer’s entry in the hall of fame.

Similarly, while the site highlights ongoing exhibits at the museum, it offers web visitors no substantial accounts of the exhibits—little or no description of the artifacts or content. A curatorial column describes the process of acquiring artifacts and planning exhibits. At the time of review, the site included a link to GuitarMania, at which artists took the familiar shape of an electric guitar and reworked it to suit their vision of the music—one of the few instances of the museum celebrating audience as well as performer. But on the whole the site offers little historical depth, and the emphasis on celebrity nostalgia makes it the cultural equivalent of relaxed fit jeans.

Michael O’Malley

Associate Professor, Dept. of History and Art History

George Mason University