talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

North American Women’s Letters and Diaries: Colonial Times to 1950

http://www.alexanderstreet.com/products/nwld.htm

Created and maintained by Stephen Rhind-Tutt.

Reviewed Dec. 29–31, 2005.

North American Women’s Letters and Diaries: Colonial Times to 1950 (nawld) is a rich database consisting of 150,000 pages culled from the letters and diaries of 1,325 North American women. The collection was conceived of by Stephen Rhind-Tutt of the Alexander Street Press and produced by the press in collaboration with the University of Chicago. Rhind-Tutt explains in his introduction that the inspiration to construct an electronic archive of women’s writings came to him while he was reading microfilmed manuscripts at the Library of Congress. Easier reading was Rhind-Tutt’s starting point, but it was not all he had in mind. He wanted to set manuscripts in type, but he also wanted to build an archive of letters and diaries whose immediacy and drama fascinated him, even if they had been previously published. “Unlike memoirs,” he thought, letters and diaries “present the raw moment without the distortions of hindsight.” Letters and diaries have their own distortions, of course, but nawld is so easy to use that it should give every visitor ample time to find references and to assess a writer’s interests and interpretative strategies.

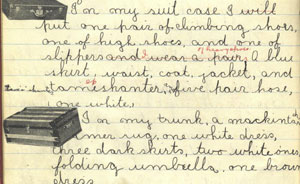

Detail from a ten year old’s diary of her journey on the Lusitania in 1910.

With limits set only by gender, geography, and its three-century chronology, nawld gathers up a wide range of writings; letters and diary entries from well-known abolitionists, activists, and writers are mixed with the ideas and experiences of anonymous women. You can read selections straight through, but the site’s useful search engine invites you to scramble the data in interesting ways. You can mix and match authors by race, religion, marital status, occupation, and place of birth. You can find accounts of the Boston Tea Party or the Boxer Rebellion. You can ignore history’s big events and retrieve documents sorted by “personal events”—"courtship,“ "loss of income,” or “physical illness of the author,” a phrase whose 1,621 matches best all others.

The full text search allows all sorts of possibilities. Type in the word “graveyard,” for example, and the site comes up with 200 matches, a letter from Emily Dickinson simply one among the 200. While the scholar of the poet may read what Dickinson had to say, others may choose to sort comments on graveyards by “frequency by year.” Here we learn that three years—1862 (23), 1944 (15), and 1865 (12)—account for a quarter of the 200 citations. I am not sure how I would bring that fact back to my students, but I might begin by reminding my sometimes date-challenged freshmen that these citations mark years with high death tolls when women might have looked on graves more often than usual. Even on more cheerful subjects, the search functions of nawld make it well suited to classroom assignments. The compilers have included images of original documents and brief biographical sketches of a number of authors. Students impatient with slow work in the archives may take real pleasure in the sense of discovery the site allows. If I had students enough and time, I might ask a class to use this Web site to explore what all the letters and diaries reveal about how being a woman shapes perception, experience, and expression.

Ann Fabian

Rutgers University

New Brunswick, New Jersey