talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

Taking the Wheel: Manufacturers’ Catalogs from the First Decade of American Automobiles

http://digitalgallery.nypl.org/nypldigital/explore/dgexplore.cfm?topic=industry&col_id=153

Created and maintained by the Digital Gallery of the New York Public Library.

Reviewed Nov. 12–16, 2008.

The New York Public Library Digital Gallery offers a vast selection of archives for browsing that includes almost three-quarters of a million digitized images, broadsides, manuscripts, maps, and rare prints. Taking the Wheel, a small subset of these electronic resources, presents nearly a thousand reproductions of motor vehicle manufacturers’ catalogs, advertisements and consumer tableaux, technical drawings, and tourist information. The exhibit is easily accessed (via thumbnails large enough for this middle-aged reviewer’s eyes) and presents a luxurious, representative sample of American car culture from the first decade of the twentieth century.

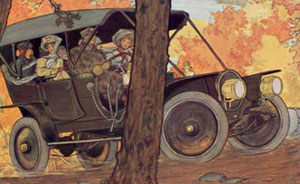

Riding in a Franklin automobile through the woods in autumn, 1909 [Image ID: 1159951]

The exhibit design is spartan yet functional. The Web site highlights a single year (1909) and organizes the documents into two groups: samples from multiple manufacturers’ catalogs (804 items) and the output of a single provider (the H. H. Franklin Manufacturing Company, 103 items). This division limits the exhibit to a reasonable sample—and 1909 is early enough in the life cycle of the automobile to capture the stunning diversity of offerings. This was a time before Fordism, before Alfred Sloan, and before the saturation point in new car sales. Indeed, when viewing the exhibit it is often difficult to set aside current knowledge of who prevailed in the American marketplace. At this rare moment, Ford, Buick, and Benz stood indistinguishable from Marmon, Jenkins, and Knox.

Sadly, little historical context is provided on the site. The references to published resources are seriously dated, which is unfortunate given the rich recent historical literature. The site does include helpful links to related New York Public Library holdings, which range from materials on ambulances and chauffeurs to taxicabs and tourists, but it misses the chance to link to other collections such as those at the Library of Congress or the Hagley Museum, which might have added greater significance to this exhibit.

While these deficiencies might disappoint the researcher, they do little to tarnish the jewels on display. The sumptuous images and diverse product lines tell a remarkable story. For example, viewers can compare the smaller, less functional runabouts that were reliant on the low-powered and patented Selden two-stroke engine to the more muscular and longer-lived touring cars, limousines, and commercial vehicles—including the Packard three-ton truck or, the not-to-be-outgunned Frontenac five-ton truck—that were propelled by the Otto four-stroke engine. Similarly, the diversity of the electric vehicles hints how their traditional carriage design and their intended function as light urban transit, primarily for women, determined their ill fate as much as the vaunted efficiency and ease of use of their internal combustion competitors. Advertising tableaux that present the products within the context of their “typical” usage are replete with class, race, and gender ideals that will have most browsers clicking for more. The elegance of the female driver in the Peerless Motorcar ads or the repose of leisure—visible in the Herreshoff motorists as they idle to watch a tennis match, or the Franklin driver taking a nature break—both challenge and sustain our understandings of the oncoming “universal car” and ubiquitous car culture. If these marketing strategies made sense to manufacturers attempting to persuade F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jay Gatsby in 1909, then how were they translated for purchasers of the Model T or a used Studebaker less than five years later? The images in Taking the Wheel provide enough comparative space, and in such a charming way, that casual patrons might begin to ask and reconceptualize these tantalizing questions.

David Blanke

Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi

Corpus Christi, Texas