talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

|

|

|

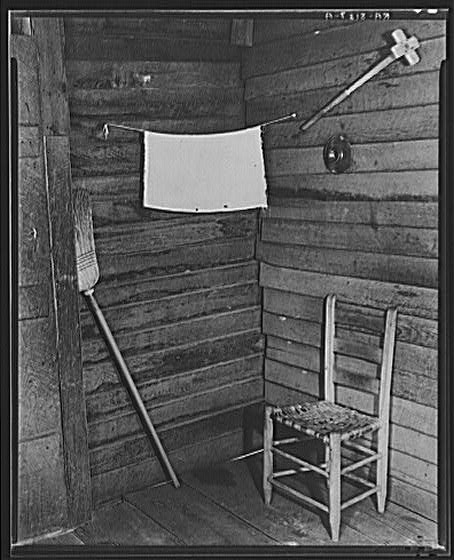

Walker Evans, kitchen corner in Floyd

Burroughs' home, Hale County, Alabama, 1936 Historians often regard photographs as a critical form of documentary evidence that hold up a mirror to past events. Public and scholarly faith in the realism of the photographic image is grounded in a belief that a photograph is a mechanical reproduction of reality. Susan Sontag captured the essence of that faith in her monumental reverie On Photography when she wrote “Photographed images do not seem to be statements about the world so much as pieces of it.” And in arranging these pieces to form historical mosaics, teachers and scholars have rarely paused to submit photographs to the usual tests applied to other forms of documentary evidence. For example, we have been trained to factor in the subjectivity of the author when we read autobiographical writing. But when we encounter an historical photograph, “shot for the record,” we often treat the image as the product of a machine and therefore an objective artifact. Since they are regarded as inherently truthful, photographs are frequently used to illustrate history textbooks. Publishers, not authors, usually select images to accompany history texts, and the images are used merely as illustrations and not as historical documents in their own right. As a consequence, today’s history students miss out on the opportunity to explore the fascinating visual dimensions of the past, to play detective with a mountain of photographic images that far outnumber traditional written documents. This essay seeks to lay out strategies for subjecting photographs to the same tests we apply to written documents when we use them as historical evidence. Exercising such scrutiny, students can bring to light the narratives hidden within images that are not always examined, despite our traditional belief that “a picture is worth a thousand words.” |

|

|

|