Not

very far from that house there is a block that is reputed to be the

worse spot in the country, and I should say it might be true from my

acquaintance with it. It was decided to tear it down long since, but

five years have passed, and the block is there still. We go slowly,

very slowly in such matters as that in New York, when there is neither

money nor politics in it. Here you are with the Italians. They live

out of doors most of the time, and that is why they are healthy though

dirty, and the death rate is not so large. Go there at sunset some evening,

and you will see an army of men and women slouching along with the unmistakable

gait of the tramp. Where they all go will puzzle you. One by one they

disappear, even while you look and before your very eyes. You will be

troubled to find what becomes of them, till you look sharp and find

doorways leading into side alleys.

Not

very far from that house there is a block that is reputed to be the

worse spot in the country, and I should say it might be true from my

acquaintance with it. It was decided to tear it down long since, but

five years have passed, and the block is there still. We go slowly,

very slowly in such matters as that in New York, when there is neither

money nor politics in it. Here you are with the Italians. They live

out of doors most of the time, and that is why they are healthy though

dirty, and the death rate is not so large. Go there at sunset some evening,

and you will see an army of men and women slouching along with the unmistakable

gait of the tramp. Where they all go will puzzle you. One by one they

disappear, even while you look and before your very eyes. You will be

troubled to find what becomes of them, till you look sharp and find

doorways leading into side alleys.

talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

|

|

|

Lewis Hine, Russian steel workers,

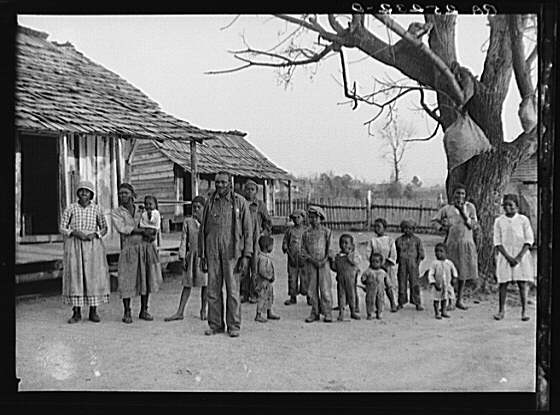

Homestead, Pa., 1908 Lewis Hine took many of his most famous photographs while working for social reform agencies, such as New York’s Charity Organization Society and the National Child Labor Committee. (The Charity Organization Society began in 1896 and the National Child Labor Committee was organized in 1904, just two of many reform organizations during the Progressive era that advocated for the amelioration of poverty, improvements to working conditions, and the end of child labor.) The reform goals of these organizations had a direct bearing on Hine’s work. In 1908 he spent three months taking photographs for the Pittsburgh Survey, a pioneering investigation of working and health conditions in that steel-producing center. Hine’s photographs illustrated the multi-volume report that caused a sensation in reform circles. In a manner similar to his photographs of immigrants at Ellis Island and child workers, Hine's Pittsburgh Survey pictures addressed the sympathies of viewers who would come across them in the pages of reform publications. Subjects such as the Russian steelworkers captured by Hine in 1908 were depicted without the wariness, the underlying fear, that characterized many of Jacob Riis's photographs of the urban poor. On the contrary, the immigrant workers in Hine’s photographs were portrayed as worthy of viewers’ sympathy, exploited and yet still dignified, deserving candidates for U.S. citizenship. Arthur Rothstein, Negroes, descendants

of former slaves of the While reformers used documentary photography to illustrate the goals of reform movements, photographs could also illustrate the biases and racist assumptions of private and government aid agencies. Arthur Rothstein took the photograph above in Gee’s Bend, Alabama, in the spring of 1937. Rothstein’s employer, the Farm Security Administration (FSA), had been providing assistance to this community of African-American sharecroppers for more than two years by the time the young government photographer arrived. Nevertheless, Rothstein was instructed to photograph the community as if there had been no such assistance granted—to capture its so-called primitive condition and thus elicit support for the kind of federal aid that the FSA was providing to rural farmers. Rothstein was told that the families at Gee’s Bend lived on an old plantation, abandoned by white owners three decades earlier. Isolated from the surrounding society, Gee’s Bend appeared to the government as a throwback to tribal society in Africa. The community was marked by a high rate of out-of-wedlock births, Rothstein was told, and the large, sprawling families lived in rude shacks that they erected themselves made of sticks and mud. The photograph above is typical of the more than fifty images Rothstein recorded during his visit. The caption for the image says that this is a single-family group. That caption implies that the sole male figure in the picture has fathered all of the children present. Both the pose and the caption stand at odds with normal FSA practice of showing small white families, lest the presence of many children put off viewers rather than enlist their sympathy. Rothstein showed no such restraint in his photographs or his captions. In a number of captions he spoke of large families of Negroes at Gees Bend, Alabama, referring to them as “Descendants of slaves of the Pettway plantation. They are still living very primitively on the plantation.” To further emphasize how the former plantation had fallen into ruin, Rothstein took the following picture of the Pettway mansion which he wrote was now “occupied by Negroes.” Arthur Rothstein, Home of the Pettways,

now inhabited by Negroes. Stripped of their didactic captions, Rothstein’s images provide visual clues suggesting that the African-American residents of Gee’s Bend lived not in a primitive society but in an economically depressed condition similar to that of white sharecroppers in the rural South. Far from proving that the hamlet’s occupants were unable to care for themselves, the images demonstrate a high level of competence and self-sufficiency. The notched log timbers of these buildings provided ample proof of the artisanal skill of the residents. As for his courtyard picture, Rothstein neglected to identify his main subject as the village elder who stood proudly before his extended family. The man was a grandfather and great grandfather, and this is a multigenerational portrait. The fathers of the children do not appear in the picture, either because Rothstein excluded them or because they were working at the time the photo was taken.

This one was called Bandit’s Roost from an old Neapolitan bandit who lived there and died there. Since then the “Roost” has been filled up by rather inoffensive Italians, who do no harm except on Sunday, when they take to playing cards and generally in the end to the knife; then murder comes in to finish the business.

Conclusion Riis’ commentary attaches very specific stories and ideas to photos that, viewed on their own, invite a variety of interpretations. While Riis and his listeners shared a strong desire to improve living conditions in poor city neighborhoods, their attitudes mirrored the prejudices of the dominant culture toward “foreigners,” as evidenced by Riis’ words and the audience reactions indicated in brackets in the transcribed text. A mix of disdain and social outrage marked Riis’ presentation of the photos. For example, he pairs a supposedly humorous account of how various ethnic groups on a block account for crime with the fact that so many more poor residents than wealthy ones die during cholera epidemics. Considering Riis’ photographs in the context that most turn-of-the-twentieth-century viewers would have experienced them—with Riis’ prejudices and reform agenda to guide their interpretations—is crucial for understanding them as historical documents.

Jacob Riisa journalist and photographer of industrial America and himself a Danish immigrantexposed the deplorable conditions of late nineteenth-century urban life in his widely-read book, How the Other Half Lives, first published in 1890. He also presented slide shows to reform-minded, middle-class audiences. Examine

four of the photographs that Riis used to accompany a lecture that

he delivered (probably in 1894) to the Washington Convention of Christians

at Work. The lecture was titled “The Other Half and How They Live;

A Story in Pictures.” Next look at the photos

alongside the words that Riis used when presenting them. (The text

excerpts are from a transcript of the lecture published in the January

1895, issue of The Temple Builder, a magazine for Christian reformers.) |

|

|

|

This

is the Fourth Ward, long given up to the worst abominations in the way

of human dwellings. That alley has a bad record. A murder was committed

there less than a week ago, and it was not the first by a great many.

In point of nationality it is typical of all down-town New York city.

When I took a census once of that alley, there were one hundred and

forty families, one hundred Irish, thirty-eight Italians, and two German,

and not a native born individual in the entire alley except the children.

No one but an Irishman could have thought of the answer one gave me

when I asked him what was the reason a policeman was always on duty

there. He said, “It’s on account of them two Dutch families

that live in the alley. They make so much trouble.” [Laughter.] A Chinaman

of whom I asked the same question outside the alley took another view

of it. He just took one look down the alley and then hurried on; “Lem

Ilish velly bad,” he said. [Laughter.] When the cholera came along

some years ago, the ratio of deaths was not over sixteen or seventeen

to the thousand in the “clean” wards up-town, but down there

in that alley it was one hundred and ninety-five to the thousand. That

is what such a place stands for in times of epidemic.

This

is the Fourth Ward, long given up to the worst abominations in the way

of human dwellings. That alley has a bad record. A murder was committed

there less than a week ago, and it was not the first by a great many.

In point of nationality it is typical of all down-town New York city.

When I took a census once of that alley, there were one hundred and

forty families, one hundred Irish, thirty-eight Italians, and two German,

and not a native born individual in the entire alley except the children.

No one but an Irishman could have thought of the answer one gave me

when I asked him what was the reason a policeman was always on duty

there. He said, “It’s on account of them two Dutch families

that live in the alley. They make so much trouble.” [Laughter.] A Chinaman

of whom I asked the same question outside the alley took another view

of it. He just took one look down the alley and then hurried on; “Lem

Ilish velly bad,” he said. [Laughter.] When the cholera came along

some years ago, the ratio of deaths was not over sixteen or seventeen

to the thousand in the “clean” wards up-town, but down there

in that alley it was one hundred and ninety-five to the thousand. That

is what such a place stands for in times of epidemic.

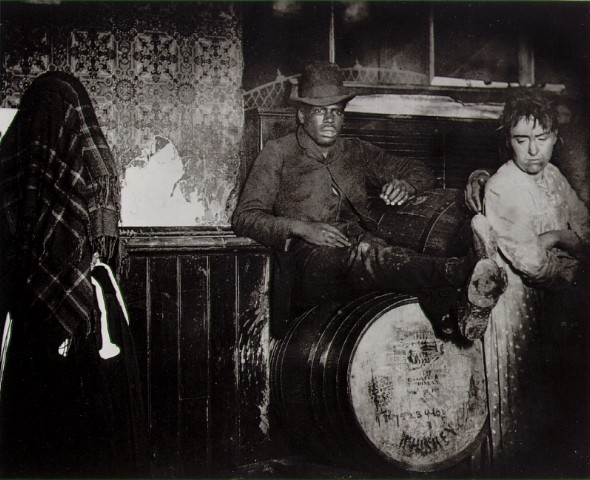

And

now we come to the bottom, down to the black-and-tan dive. When the

black and white of both sexes meet on such ground, then you have the

abomination than which there is none more vile. From there the descent

is very easy to the rogue’s gallery.

And

now we come to the bottom, down to the black-and-tan dive. When the

black and white of both sexes meet on such ground, then you have the

abomination than which there is none more vile. From there the descent

is very easy to the rogue’s gallery.