talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

|

|

| Many of America’s most famous documentary photographs have resulted from a photographer’s ability to capture a compelling scene, whether by arranging subject matter or experimenting with alternate compositions. This active direction might continue well after the scene was frozen on film. Photographers could add material after the fact, most often titles or descriptive captions designed to direct the gaze of prospective viewers and underscore the image’s intended meaning. Such was clearly the case with Jacob Riis’ Bandit’s Roost. Riis knew at the time of exposure how he would use this image. He would transform the photograph into a lantern slide to illustrate one of his famous reform lectures. Riis embellished these lectures with an exaggerated vocabulary of which this title is but one example. In so doing, Riis created powerful interpretive frameworks for the way viewers understood the photographs in his lantern slide lectures. The photographs drove home his message; in return, the phrases that proved popular with Riis’ audience could serve as titles for subsequent pictures. Lewis Hine employed similar strategies in his photographs of newly arrived immigrants and downtrodden factory workers. Like Riis, Hine placed great faith in the power of accompanying words to drive home the point of his images. Lewis Hine, One Arm and Four Children,

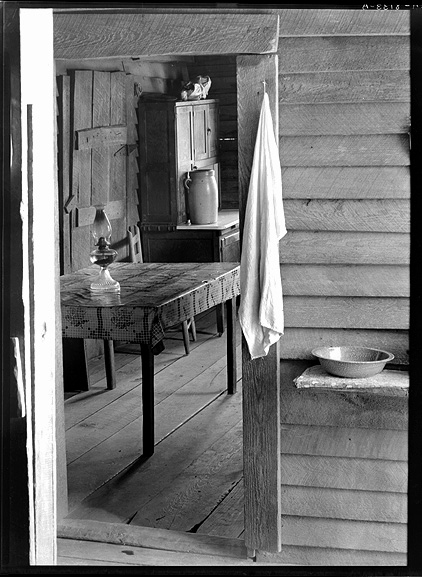

1910 Hine recorded the photograph above for the section of the Pittsburgh Survey that dealt with industrial accidents. To illustrate how families were victimized when the head of the household could no longer work, Hine posed an amputee father in the foreground with the man’s wife and four children slightly to the rear. From a standpoint of composition and aesthetic design, the image left much to be desired. Although Hine made willing subjects of this man and his family, the poses were awkward and the facial expressions of the children threatened to undercut the pathos that Hine intended. Hine overcame these obstacles by providing a caption for the picture that riveted viewers’ attention on the problem of industrial accidents. He labeled the image One Arm and Four Children. In this and other photographs for the Pittsburgh Survey, Hine borrowed the language of the reformers and affixed it to his images. In so doing he fused the power of the raw image with the persuasiveness of the written word. By contrast, Walker Evans steadfastly refused to title his photographs or to attach descriptive captions. In 1941, he and James Agee published Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, a collaboration since hailed as America’s premier work of documentary reportage. Unlike Hine’s photographs for the Pittsburgh Survey, Evans’ images stand alone at the beginning of the book. They were not designed to illustrate Agee’s text, and the images bear no captions whatsoever. When the photograph below appeared in the second edition of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, it was part of a series of images of the Burroughs family (identified pseudonymously in the text as the Gudgers) and their home. Careful reading of Agee’s precise description of the Burroughs’ home reveals evidence of the arrangements Evans made to craft the image of the kitchen corner. Evans removed a bench from along the wall and brought a caned chair from across the room to stand in its stead, and he moved the large crockery vessel (probably a butter churn) onto the cupboard. He also likely cleared the table of its place settings, since Agee describes the family’s habit of placing their dishes back on the table after washing them. In this case, while Agee’s words were not presented directly with the photographs, they still provide clues that help viewers to interpret the photo as a reflection of Evans’ vision as much as a document of the Burroughs’ environment. Walker Evans, 1936

|

|

|

|