talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

If we are to determine the meaning of a documentary photograph we must begin by establishing the historical context for both the image and its creator. A documentary photographer is an historical actor bent upon communicating a message to an audience. Documentary photographs are more than expressions of artistic skill; they are conscious acts of persuasion. The work of the most accomplished photographers reveals a fervent desire to let images tell a story. Documentarians from Mathew Brady to Dorothea Lange succeeded because they understood the desires of their audience and did not shy from molding their images accordingly. Far from being passive observers of the contemporary scene, documentary photographers were active agents searching for the most effective way to communicate their views. The following examples show how Jacob Riis used his camera not only to amass a quantity of sociological data but to assert his own assessment of immigrants and tenement life in New York City. Although Jacob Riis did not have an official sponsor for his photographic work, he clearly had an audience in mind when he recorded his dramatic urban scenes. Author of popular newspaper stories and the book How the Other Half Lives, an indictment of the living conditions of immigrant workers in New York City’s Lower East Side neighborhood, Riis was much in demand as a lecturer. He converted many of his images into lantern slides that he used to great effect in his impassioned presentations. He no doubt had his middle-class clientele in mind when composing his pictures. Despite his own immigrant background, Riis’ attitudes mirrored the prejudices of the dominant culture toward “foreigners.” His reports on immigrant life–and his equally famous photographs–were important documents of urban conditions in late nineteenth-century urban America. But they were equally revealing as documents that showed how outsiders often reacted in horror to people who composed “the other half.” In his famous 1888 photograph Bandit’s Roost (probably taken by an associate in an alley off of Mulberry Street in what is now New York’s Chinatown district), Riis argued that the alley, like the tenement, was a breeding ground for disorder and criminal behavior.

Jacob A. Riis, Bandit's Roost, 1888 At first glance, the foreground figures in the photograph underscore the aura of menace created by Riis’ caption. Two men appear to guard the alley entrance. Perched on the railing of the right-hand staircase is a third man who has assumed a casual, yet commanding, pose. Perhaps he is the ringleader of this gang. But what of the other ten figures in the image, the women leaning out the windows, the young child in the right background, the three figures on the opposite porch? There is nothing in their demeanor that suggests criminal behavior. If they were indeed part of a notorious gang, why would they be so willing to pose for the camera, especially since members of the police force often accompanied Riis on his photographic forays? How did Riis secure the cooperation of all these individuals? Certainly not by telling them that he wanted a picture of notorious criminals. Is this really a den of iniquity, as Riis would have us believe? In the background of the image, long lines of laundry stretch between the buildings. Riis was fond of saying that “the true line to be drawn between pauperism and honest poverty is the clothesline. With it begins the effort to be clean that is the first and best evidence of a desire to be honest.” Like many documentary photographers who followed him, Jacob Riis employed children as symbols of society’s neglect. Riis called his small subjects “Street Arabs” thereby engaging powerful middle-class sentiments about both exoticism and itinerancy. “The Street Arab has all the faults and all the virtues of the lawless life he leads,” Riis warned his readers in his 1890 exposé How the Other Half Lives. But how did Riis gain the cooperation of these stealthy and suspicious subjects? He hired the young “toughs” in this picture to reenact a common crime by having them mug one of their own. He then paid all the boys with cigarettes.

Jacob A. Riis (Richard Hoe Lawrence), A Growler Gang in Session (Robbing a Lush), 1887 Riis did not limit such arrangements to the street toughs but posed more than a half a dozen images of young boys sleeping in stairwells and doorways. The pictures appear to have been taken in broad daylight and the small subjects are obviously pretending to be asleep. Whether they were indeed homeless remains a question open to modern viewers, but not one likely to have been asked by the photographer’s contemporaries. Jacob A. Riis, Street Arabs in Sleeping

Quarters, c. 1880s

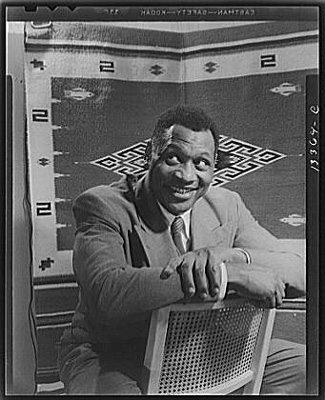

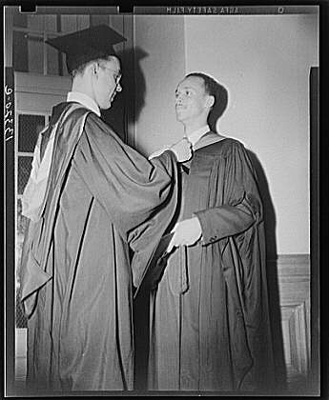

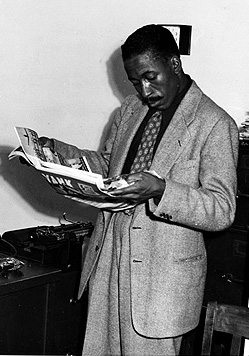

Gordon Parks, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information photographer, c. 1943 In a society segregated by race, Gordon Parks’ identity and experiences as an African-American man indelibly influenced his documentary photography work. As a young man, Parks worked as a waiter on passenger trains and a jazz musician, and he taught himself photography. In 1941 he won a Julius Rosenwald fellowship and chose to apprentice for a year under Roy Stryker at the Farm Security Administration. (The Rosenwald Fund provided grants to promising African-American scholars and artists.) The FSA had never employed an African-American photographer, and Stryker initially resisted taking on Parks, fearing the reaction of FSA staffers. But the Rosenwald Fund, with its close political connections to the Roosevelt administration, prevailed, and Parks arrived in Washington in January 1942. The young photographer, raised in Kansas City and well-traveled from his railroad days, found a city that, in his later words, “bulged with racism.” In his 1990 autobiography Voices in the Mirror, Parks recalled how he was treated in this “hate-drenched city”: “Eating houses shooed me to the back door; theaters refused me a seat, and the scissoring voices of white clerks at Julius Garfinckel’s prestigious department store riled me with curtness. Some clothing I had hoped to buy went unbought. They just didn’t have my size—no matter what I wanted.”* Furious, he swore to Stryker that he would document this shocking level of bigotry in a city that contained the symbols of American democracy. He soon realized that “photographing bigotry was very difficult,” and so he focused on “the evil of its effect...discernible in the black faces of the oppressed and their blighted neighborhood lying within the shadows of the Capitol.”* Parks’ work was shaped by own experiences, his conversations with African-American residents of Washington, and his close study of the work of fellow FSA photographers such as Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Arthur Rothstein, and Walker Evans. He also cited Richard Wright’s Twelve Million Black Voices, a 1941 exploration of the lives of African Americans during the Great Depression that featured the work of FSA photographers, as “my bible, a big part of my learning, and the inspiration needed to keep my camera moving where it might do the most good.” Gordon Parks took these photos in Washington, D.C., in 1942.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

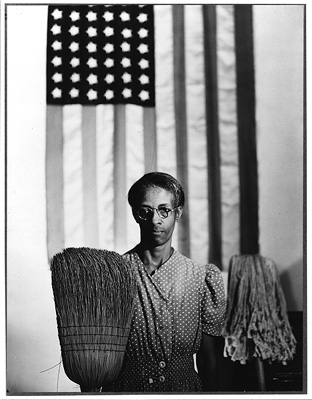

Following

Roy Stryker’s advice to talk to African-American residents of

Washington about their experiences of the city’s racism, Parks

struck up a conversation one night with Ella Watson, a cleaning

woman in the government office building that housed the FSA. This

image, titled “American Gothic,” became Parks’ most famous photo

and an emblem of Jim Crow segregation. Posing Watson holding a

broom and mop in front of an American flag, he echoed the pose

of Grant Wood’s famous “American Gothic” painting (which depicts

a stern looking farm couple holding a pitchfork in a similar pose)

and used it to visually dramatize the existence of racial discrimination

in a supposedly democratic society.

Following

Roy Stryker’s advice to talk to African-American residents of

Washington about their experiences of the city’s racism, Parks

struck up a conversation one night with Ella Watson, a cleaning

woman in the government office building that housed the FSA. This

image, titled “American Gothic,” became Parks’ most famous photo

and an emblem of Jim Crow segregation. Posing Watson holding a

broom and mop in front of an American flag, he echoed the pose

of Grant Wood’s famous “American Gothic” painting (which depicts

a stern looking farm couple holding a pitchfork in a similar pose)

and used it to visually dramatize the existence of racial discrimination

in a supposedly democratic society.