talking history | syllabi | students | teachers | puzzle | about us

|

|

| Documentary photographers rarely take a single photograph of a given subject. If only to ensure that they have backups for their master composition, they usually take a series of pictures and later select the one image that best relates their sense of the scene. In this selection process they may decide to save the “outtakes” (as they are called in the film industry) or to destroy them lest they distract attention from their chosen image. FSA photographers had no such opportunity to edit their own work. Government regulations required them to turn in all pictures from an assignment. The FSA collection therefore offers scholars an unparalleled opportunity to place masterworks, such as Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother (1936), in the context of companion images taken on the same day. (See activity below.) This visual evidence offers a much more reliable guide to the photographer’s original intent than the artist’s recollections recorded decades after the fact. Companion images to another famous FSA photograph, Russell Lee’s Christmas Dinner in Iowa (1936), would suffer a similar fate. Lee was by far the most prolific of Roy Stryker’s photographers and certainly the most well-traveled. Shortly after joining the photographic project, he accepted an assignment to document the lives of white sharecroppers in rural Iowa. Near the small hamlet of Smithland, Lee took a series of pictures of a tenant farmer struggling to make a living on a landscape that had been ravaged by drought. The photograph below shows the farmer’s children standing at a table eating dinner on Christmas day. The place at the head of the table is vacant and the image raises the troubling prospect of parental abandonment. Lee took another photograph of this meager meal, this one showing the father in his accustomed place at the head of the table. Russell Lee, Christmas Dinner in Iowa,

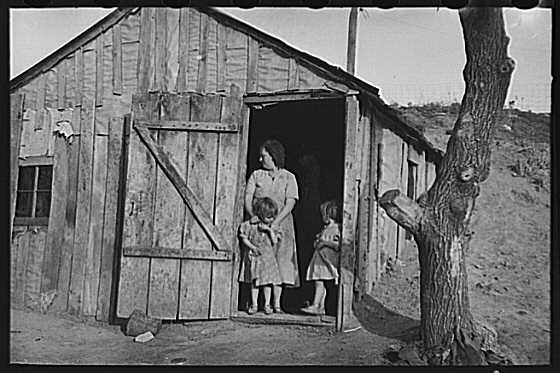

1936 The picture above became an instant classic in part because it provided a startling counterpoint to more common images of a bounteous holiday feast spread out before a thankful family. Long after his retirement from government service, Lee was asked about the circumstances surrounding Christmas Dinner in Iowa. Lee remembered the name of the farmer, Earl Pauley, and recalled taking a number of pictures on the farm. He told an interviewer that Pauley was a widower and was doing his best to provide for his needy children. These recollections added power and poignancy to Lee’s portrait. Yet in this instance, Lee’s memory betrayed him, for the FSA file contains a photograph of Pauley’s wife standing in the doorway of the shack with two of the children who later posed for the dinner photograph. This hitherto unpublished image provides clear evidence that Lee assigned places at the dinner table. He asked the father to step out of the scene but never made room for the mother. Her presence would have undercut the dramatic scene that Lee had in mind. Russell Lee, Mrs. Earl Pauley and

some of her children, 1936

One of the most enduring images of the Depression is a portrait of a woman and her children in a California migrant labor camp. Taken by FSA photographer Dorothea Lange, it was the last of a series of six photographs that Lange shot on a rainy afternoon in March 1936. Beginning with “Migrant Mother,” the image Lange published and exhibited, all the photographs in the series are presented here, but not in the order that Lange originally took them. Consider what Lange wanted to convey in “Migrant Mother” and choose the sequence you think led up to it in the photo session. |

|

|

|